Superregnum: Eukaryota

Cladus: Unikonta

Cladus: Opisthokonta

Cladus: Holozoa

Regnum: Animalia

Subregnum: Eumetazoa

Cladus: Bilateria

Cladus: Nephrozoa

Superphylum: Deuterostomia

Phylum: Chordata

Subphylum: Vertebrata

Infraphylum: Gnathostomata

Megaclassis: Osteichthyes

Cladus: Sarcopterygii

Cladus: Rhipidistia

Cladus: Tetrapodomorpha

Cladus: Eotetrapodiformes

Cladus: Elpistostegalia

Superclassis: Tetrapoda

Cladus: Reptiliomorpha

Cladus: Amniota

Cladus: Synapsida

Cladus: Eupelycosauria

Cladus: Sphenacodontia

Cladus: Sphenacodontoidea

Cladus: Therapsida

Cladus: Theriodontia

Cladus: Cynodontia

Cladus: Eucynodontia

Cladus: Probainognathia

Cladus: Prozostrodontia

Cladus: Mammaliaformes

Classis: Mammalia

Subclassis: Trechnotheria

Infraclassis: Zatheria

Supercohors: Theria

Cohors: Eutheria

Infraclassis: Placentalia

Cladus: Boreoeutheria

Superordo: Euarchontoglires

Ordo: Primates

Subordo: Strepsirrhini

Infraordo: Lemuriformes

Superfamilia: Lemuroidea

Familia: Cheirogaleidae

Genus: Phaner

Species: P. electromontis – P. furcifer – P. pallescens – P. parienti

Name

Phaner Gray, 1870

Type species: Lemur furcifer Blainville, 1839

Phaner furcifer

References

Phaner in Mammal Species of the World.

Wilson, Don E. & Reeder, DeeAnn M. (Editors) 2005. Mammal Species of the World – A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. Third edition. ISBN 0-8018-8221-4.

Cat. Monkeys, Lemurs, Fruit-eating Bats Brit. Mus., p. 135.

Wilson, D.E. & Reeder, D.M. (eds.) 2005. Mammal Species of the World: a taxonomic and geographic reference. 3rd edition. The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore. 2 volumes. 2142 pp. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. Reference page.

Vernacular names

Deutsch: Gabelstreifenmaki

English: Fork-marked Lemur

日本語: フォークキツネザル属

lietuvių: Šakotajuosčiai lemūrai

Nederlands: Vorkstreepmaki

Fork-marked lemurs or fork-crowned lemurs are strepsirrhine primates; the four species comprise the genus Phaner. Like all lemurs, they are native to Madagascar, where they are found only in the west, north, and east sides of the island. They are named for the two black stripes which run up from the eyes, converge on the top of the head, and run down the back as a single black stripe. They were originally placed in the genus Lemur in 1839, later moved between the genera Cheirogaleus and Microcebus, and given their own genus in 1870 by John Edward Gray. Only one species (Phaner furcifer) was recognized, until three subspecies described in 1991 were promoted to species status in 2001. New species may yet be identified, particularly in northeast Madagascar.

Fork-marked lemurs are among the least studied of all lemurs and are some of the largest members of the family Cheirogaleidae, weighing around 350 grams (12 oz) or more. They are the most phylogenetically distinct of the cheirogaleids, and considered a sister group to the rest of the family. Aside from their dorsal forked stripe, they have dark rings around their eyes, and large membranous ears. Males have a scent gland on their throat, but only use it during social grooming, not for marking territory. Instead, they are very vocal, making repeated calls at the beginning and end of the night. Like the other members of their family, they are nocturnal, and sleep in tree holes and nests during the day. Monogamous pairing is typical for fork-marked lemurs, and females are dominant. Females are thought to have only one offspring every two years or more.

These species live in a wide variety of habitats, ranging from dry deciduous forests to rainforests, and run quadrupedally across branches. Their diet consists primarily of tree gum and other exudates, though they may obtain some of their protein and nitrogen by hunting small arthropods later at night. All four species are endangered. Their populations are in decline due to habitat destruction. Like all lemurs, they are protected against commercial trade under CITES Appendix I.

Taxonomy

Fork-marked lemurs were first documented in 1839 by Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville when he described the Masoala fork-marked lemur (P. furcifer) as Lemur furcifer.[6][7] The holotype is thought to be MNHN 1834-136, a female specimen taken from Madagascar by French naturalist Jules Goudot. The source of this specimen is unknown, but thought to be Antongil Bay.[8] In 1850, Isidore Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire moved the fork-marked lemurs to the genus Cheirogaleus (dwarf lemurs),[9] but they were also commonly listed in the genus Microcebus (mouse lemurs).[10] In 1870, John Edward Gray assigned fork-marked lemurs to their own genus, Phaner,[6] after initially including them and the mouse lemurs in the genus Lepilemur (sportive lemurs). Although French naturalist Alfred Grandidier accepted Gray's new genus (while also lumping the other cheirogaleids in Cheirogaleus and illustrating the cranial similarities between cheirogaleids and Lepilemur) in 1897,[11] the genus Phaner was not widely accepted. In the early 1930s, Ernst Schwarz, Guillaume Grandidier, and others resurrected the name, citing characteristics that were intermediate between Cheirogaleus and Microcebus.[12]

Until the late 20th century, there was only one recognized species of fork-marked lemur,[6] although size and coloration differences had been noted previously.[8] After comparing museum specimens, paleoanthropologist Ian Tattersall and physical anthropologist Colin Groves recognized three new subspecies in 1991: the Pale fork-marked lemur (P. f. pallescens), Pariente's fork-marked lemur (P. f. parienti), and the Amber Mountain fork-marked lemur (P. f. electromontis).[6][13] In 2001, Groves elevated all four subspecies to species status[6][14] based on noticeable color, size, and body proportion differences between the fragmented populations. Although Tattersall disagreed with this promotion, citing inadequate information for the decision,[15] the arrangement is generally accepted.[6]

In December 2010, Russell Mittermeier of Conservation International and conservation geneticist Edward E. Louis Jr. announced the possibility of a new species of fork-marked lemur in the protected area of Daraina in northeast Madagascar. In October, a specimen was observed, captured, and released, although genetic tests have yet to determine if it is a new species. The specimen demonstrated a slightly different color pattern from other fork-marked lemur species. If shown to be a new species, they plan to name it after Fanamby, a key conservation organization working in that protected forest.[16][17]

Etymology

The etymology of the genus Phaner puzzled researchers for many years. Gray often created mysterious and unexplained taxonomic names. In 1904, Theodore Sherman Palmer attempted to document the etymologies of all mammalian taxa, but could not definitively explain the origins of the generic name Phaner, noting only that it derived from the Greek φανερός (phaneros) meaning "visible, evident". In 2012, Alex Dunkel, Jelle Zijlstra, and Groves attempted to solve the mystery. Following some initial speculation, a search of the general literature published around 1870 revealed the source: the British comedy The Palace of Truth by W. S. Gilbert, which premiered in London on 19 November 1870, nearly one and a half weeks prior to the date written on the preface of Gray's manuscript (also published in London). The comedy featured characters bearing three names: King Phanor (sic), Mirza, and Azema. Since the genera Mirza (giant mouse lemurs) and Azema (for M. rufus, now a synonym for Microcebus) were both described in the same publication and equally enigmatic, the authors concluded that Gray had seen the comedy and then based the names of three lemur genera on its characters.[18]

Fork-marked lemurs were called "fork-marked dwarf lemurs" by Henry Ogg Forbes in 1894 and "fork-crowned mouse lemur" by English missionary and naturalist James Sibree in 1895. Literature searches by Dunkel et al. also uncovered other names, such as "fork-lined lemur" and "squirrel lemur", during the early 1900s. By the 1970s, reference to dwarf and mouse lemurs had ended, and the "fork-crowned" prefix became popular between 1960 and 2001. Since then, the "fork-marked" prefix has become more widely used.[18] These lemurs get their common name from the distinctive forked stripe on their head.[6]

Evolution

Competing phylogenies

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Fork-marked lemurs are either a sister group within Cheirogaleidae (top—Weisrock et al. 2012)[19] or more closely related to sportive lemurs (bottom—Masters et al. 2013).[20]

Within the family Cheirogaleidae, fork-marked lemurs are the most phylogenetically distinct, although their placement remained uncertain until recently.[21] One uniting characteristic (synapomorphy) among all cheirogaleids, to the exclusion of other lemurs, is the branching of the carotid artery along with how it enters the skull[22]—a trait which is shared by fork-marked lemurs.[21] Analyses based on morphology, immunology, and repetitive DNA have given contradictory placements of Phaner, while studies in 2001 and 2008 either lacked data or yielded poor resolution of their placement.[19]

A study in 2009 of seven mitochondrial genes (mtDNA) and three nuclear genes grouped fork-marked lemurs with sportive lemurs (family Lepilemuridae), offering a host of explanations, such as a possible hybridization (introgression) following the initial split between the families.[21] A study published in 2013 also grouped fork-marked lemurs with sportive lemurs[23] when it used 43 morphological traits and mtDNA.[24] If correct, this would make the family Cheirogaleidae paraphyletic.[23] Broad agreement between two lemur phylogeny studies—one in 2004 using SINE analysis and another in 2012 using multilocus phylogenetic tests—gave strong support for a sister group relationship between fork-marked lemurs and the rest of the cheirogaleids and a more distant relationship with sportive lemurs.[19] The split between Phaner and the rest of the cheirogaleids is thought to have occurred approximately 38 mya (million years ago), not long after the radiation of most of the major lemur groups on Madagascar, roughly 43 mya.[25][26]

Description

Black-and-white drawing of two fork-marked lemurs walking quadrupedally through the trees.

P. furcifer, first described in 1839, was illustrated in Brehms Tierleben.

Of the mostly small, nocturnal lemurs in family Cheirogaleidae, the genus Phaner contains some of the largest species, along with Cheirogaleus.[6] Their body weight ranges between 350 and 500 g (0.77 and 1.10 lb),[27] and their head-body length averages between 23.7 and 27.2 cm (9.3 and 10.7 in), with a tail length between 31.9 and 40.1 cm (12.6 and 15.8 in).[28]

Fork-marked lemurs' dorsal (back) fur is either light brown or light grayish-brown, while their ventral (underside) fur can be yellow, cream, white, or pale brown.[6][8] A black stripe extends from the tail, along the dorsal midline to the head, where it forks at the top of the head in a distinguishing Y-shape leading to the dark rings around both eyes, and sometimes extends down the snout. The dorsal stripe varies in width and darkness.[6][29] The base of the tail is the same color as the dorsal fur[27] and is usually tipped in black;[6][27] the tail is bushy.[27][30] The lemurs' ears are relatively large and membranous.[30] Males have a scent gland on the middle of their throat,[27] which is approximately 20 mm (0.79 in) wide and pink in color. Females have a narrow, bare patch of white skin in the same location, but theirs does not appear to produce secretions.[31]

These lemurs have relatively long hindlegs. For gripping tree trunks and large branches, they have large hands and feet with extended pads on the digits, as well as claw-like nails.[30][32] They have a long tongue which assists obtaining the gum and nectar,[30][32] as well as a long caecum, which helps digest gums.[6][30] Their procumbent (forward-facing) lemuriform toothcomb (formed by the lower incisors and canines) is long[32] and more compressed, with significantly reduced interdental spaces to minimize the accumulation of gum between the teeth.[33]

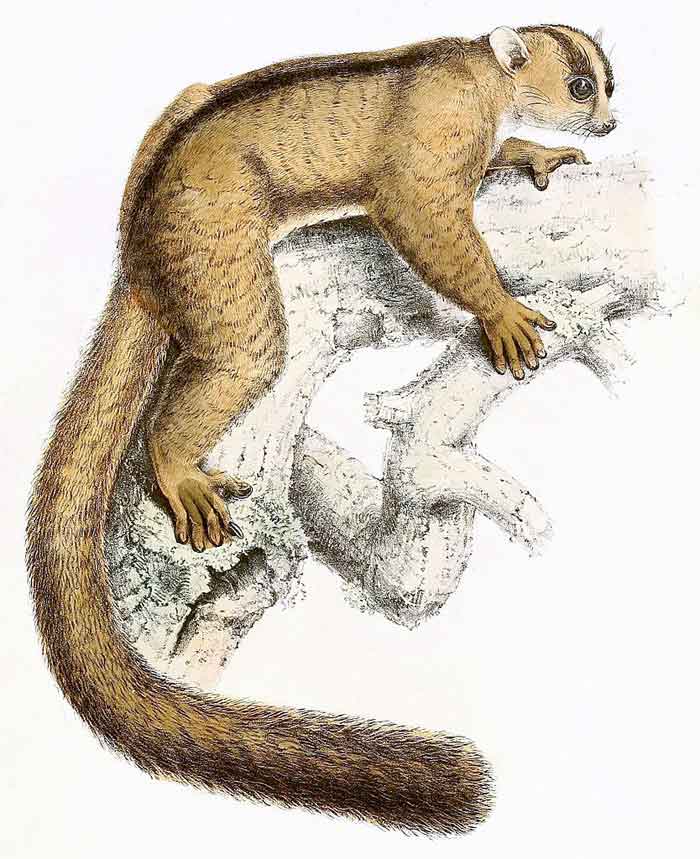

Illustration of a fork-marked lemur positioned horizontally on a branch.

Fork-marked lemurs are distinguished by the dorsal black stripe that forks on the crown of their head.

The genus is distinguished from other cheirogaleids by the toothrows on its maxilla (upper jaw), which are parallel and do not converge towards the front of the mouth.[14] The fork-marked lemur dental formula is 2.1.3.32.1.3.3 × 2 = 36; on each side of the mouth, top and bottom, there are two incisors, one canine, three premolars, and three molars—a total of 36 teeth.[34] Their upper first incisor (I1) is long and curved towards the middle of the mouth (unique among lemurs),[14][34] while the second upper incisor (I2) is small with a gap (diastema) between the two.[34] The upper canines are large, with their tips curved.[14][34] Their upper anterior premolars (P2) are caniniform (canine-shaped)[30][32] and more pronounced than in any other living lemur.[35] The next upper premolar (P3) is very small,[14] with a single, pointed cusp that contacts the lingual cingulum (a crest or ridge on the tongue side), which circles the base of the tooth. The two cusps on the last upper premolar (P4) are a large paracone and a smaller protocone. Like other cheirogaleids, their first lower premolar (P2) is caniniform and large, while the cingulids (ridges) on the three lower premolars are more developed compared to most other cheirogaleids. The first two upper molars (M1–2) have a developed hypocone, and the buccal cingulum (a crest or ridge on the cheek side) is well developed on all three upper molars.[35] The molars are relatively small compared to other cheirogaleids, with the second upper and lower molars (M2 and M2) having reduced functionality compared to those of mouse lemurs.[9]

Males have relatively small testes compared to other lemurs, and their canine teeth are the same size as those seen in females. During the dry season, females can weigh more than males. Both patterns of sexual dimorphism are consistent with the theory of sexual selection for monogamous species and female dominance respectively.[36] Females have two pairs of nipples.[36]

Distribution and habitat

Fork-marked lemurs are found in the west, north, and east of Madagascar, but their distribution is discontinuous.[6][30] Their habitat ranges from dry deciduous forests on the western coast of the island to rainforest in the east.[32] They are also commonly found in secondary forest, but not in areas lacking continuous forest cover.[37] They are most common in the west of the island.[30] Fork-marked lemurs are not found in the southern spiny forests in the dry southern part of the island, and only recently have been reported from the southeastern rainforest at Andohahela National Park, though this has not been confirmed. A team led by E. E. Louis Jr. has suggested that undescribed varieties may also exist elsewhere on the island.[6]

The Masoala fork-marked lemur is found on the Masoala Peninsula in the northeast of the island,[38] while the Amber Mountain fork-marked lemur is located in the far north of the island, particularly at Amber Mountain National Park.[39] Pariente's fork-marked lemur is found in the Sambirano region in the northwest,[40] and the pale fork-marked lemur is in the west of the island.[41]

Behavior

View of a male fork-marked lemur in a tree from underneath, showing the scent gland on the throat.

Males, such as this P. pallescens, have a scent gland on their throat, which they only use during social grooming.

Fork-marked lemurs are among the least studied of all lemurs, and little is known about them.[6] Only the pale fork-marked lemur (P. pallescens) has been studied relatively well, primarily by Pierre Charles-Dominique, Jean-Jacques Petter, and Georges Pariente during two expeditions in the 1970s and a more extensive 1998 study in Kirindy Forest.[42] Like the other cheirogaleids, these lemurs are nocturnal, sleeping in tree hollows (typically in large baobab trees) or abandoned nests built by giant mouse lemurs (Mirza coquereli) during the day.[37][30][43] Some of the abandoned nests they sleep in are leaf-lined, and fresh leaves are often added when young are born. As many as 30 sleeping sites may be used over the course of a year, each for a variable length of time.[42]

At night, fork-marked lemurs visit the feeding sites within their range by running quadrupedally across branches[30] at high speed over long distances,[44] leaping from tree to tree without pausing.[6] They have been seen on the ground (typically during chases following fights)[37][44] and as high as 10 m (33 ft), but they are typically seen running along branches at a height of 3 to 4 m (9.8 to 13.1 ft).[37] While running, they can leap 4 to 5 m (13 to 16 ft) horizontally between tree branches without losing height or as much as 10 m (33 ft) while falling a short distance.[45]

Fork-marked lemurs are sensitive to light intensity,[44] and emerge at twilight, calling numerous times and answering their neighbors' calls before going off to forage.[32][44] Just before dawn, they also communicate again on their way to their sleep site. Cold temperatures can also cause individuals to retire to their sleeping site as early as two hours before dawn.[44] Their eye shine creates a unique pattern among lemurs because they tend to bob their heads up and down and from side to side.[6]

Illustration showing the profile of 9 lemur species from both Cheirogaleidae or Lepilemuridae, demonstrating the similarities in skull shape

In 1897, Alfred Grandidier demonstrated the similarities between Lepilemur (middle column, bottom two) and the cheirogaleids, particularly Phaner (middle, top).

These lemurs are territorial, with territory size dependent upon food availability,[46] though territories typically cover 3 to 10 hectares (7.4 to 24.7 acres). Because of their fast movement, individuals can easily defend their territories by traversing it within 5 minutes.[44] Territory overlap is minimal between males, and the same pattern is seen in females, though males and females may overlap their territories.[46] In areas where territory overlap occurs ("meeting areas"), several neighbors may gather and vocalize together without aggression.[37][36][47] Multiple family groups may gather in these meeting areas, and females will often socialize with the other females and young.[36] Unlike other lemurs, fork-marked lemurs do not scent-mark, and instead use vocalizations during territorial confrontations.[48] They are considered very vocal animals, and have a complex range of calls.[6] On average, males make approximately 30 loud calls per hour,[37][43] and are most vocal at dusk and dawn. Their high-pitched, whistling calls help researchers identify them in the field.[6] As well as their stress call and fighting call, they emit a Hon call (contact call between male-female pairs), Ki and Kiu calls (more excited contact calls that identify the caller), and a Kea call (a loud call shared between males in adjacent territories). Females also make a "bleating" call when they have infants.[49]

Males and females have been seen sleeping and foraging together as monogamous pairs, although polygamy and solitary behavior has also been observed.[50] At Kirindy Forest, pairs were observed staying together for multiple seasons, though they were only seen foraging alone, with most interactions resulting from conflicts over feeding sites.[44] Nest sharing among pairs occurs one out of every three days.[44] During social grooming (allogrooming), the male allomarks females using a scent gland on the throat,[51] and grooming sessions can last several minutes.[44] While feeding, females appear to be dominant, gaining first access to food.[52] Females are also dominant over non-resident males, indicating true female dominance, comparable to that seen in the ring-tailed lemur (Lemur catta).[36]

Mating has been observed to take place at the end of the dry season, in early November, and births were inferred between late February and early March.[36] Only one infant is born per season,[37][36] despite females having two pairs of nipples.[36] Infants are initially parked in unguarded tree holes while the mother forages.[36][53] Older infants have not been observed clinging to the mother, and as they get older, they are parked in vegetation until they can move independently. Females produce milk for two years following the birth of the young.[36] The offspring may remain under the care of their parents for three years or more,[44] and there is no information about their dispersal at maturity. Females have not been observed giving birth in consecutive years.[36]

Ecology

These lemurs have a specialized diet of tree gums and sap.[6][54] Their diet consists mainly of gum from trees in the genus Terminalia (known locally as "Talinala"),[6][42][55] which are often parasitized by beetle larvae that burrow beneath the bark. Fork-marked lemurs either consume the gum as it seeps from cracks in the bark of parasitized trees or gouge open the bark with their toothcomb to scoop it up directly with their long tongue. Between March and May, gums compose the majority of the diet.[6][32] They have also been documented eating gums from Commiphora species and Colvillea racemosa, bud exudates from Zanthoxylum tsihanimposa, sap from baobab trees (Adansonia species),[32] nectar from Crateva greveana flowers, the sugary excretions from bugs (family Machaerotidae) which feed on trees of the genus Rhopalocarpus,[6][32][44] and very small amounts of fruit.[44] Although fork-marked lemurs have widely varied forest habitat, gum and other plant exudates of other species are likely to dominate their diet.[32] They are not known to estivate or accumulate fat reserves for the dry season.[45]

Madagascar harrier-hawk sits perched over a tree hole.

The Madagascar harrier-hawk may prey on fork-marked lemurs by extracting them from their sleeping holes.

To meet their protein requirements and obtain nitrogen, these lemurs also hunt small arthropods. In captivity, P. furcifer strongly favored preying mantises and moths of the family Sphingidae while ignoring grasshoppers, larva of the moth genus Coeloptera, and small reptiles. Hunting usually occurs later at night, following gum collection, and typically happens in the canopy or on tree trunks. Insects are captured by rapidly grasping them with the hands, a stereotypic behavior seen in other members of their family, as well as galagos.[56] The exudates of several tree species they are known to feed on are high in protein, so some fork-marked lemurs may meet their protein requirements without preying on insects.[44]

Other nocturnal lemurs are sympatric with fork-marked lemurs. In western Madagascar, interspecific competition is reduced by restricting activity to specific levels of the canopy, such as using only the highest sleeping sites at least 8 m (26 ft) above the ground. Competition with other cheirogaleids, such as the gray mouse lemur (Microcebus murinus) and Coquerel's giant mouse lemur (Mirza coquereli), is most intense for Terminalia gum during the dry season, but fork-marked lemurs always drive the other lemur species off.[42] Studies of P. pallescens at Kirindy Forest found up to a 20% drop in body mass during the dry season despite no changes in exudate production, indicating flowers and insects have a significant impact on the species' health.[44]

Fork-marked lemurs are thought to be preyed upon by large owls, such as the Madagascar owl (Asio madagascariensis), and snakes like the Malagasy tree boa (Sanzinia madagascariensis).[43] In one case, a family of fork-marked lemurs exhibited mobbing behavior when they encountered a Malagasy tree boa.[44] Diurnal raptors, such as the Madagascar buzzard (Buteo brachypterus) and Madagascar cuckoo-hawk (Aviceda madagascariensis) hunt these lemurs at dusk,[43][44] and the hunting behavior of the Madagascar harrier-hawk (Polyboroides radiatus) suggests it might extract them from their sleeping holes. The fossa (Cryptoprocta ferox) has also been seen attacking fork-marked lemurs, and remains have been found in their scat.[44]

Conservation

In 2020, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) listed all four species as endangered.[57][58][59][60] Before this assessment, it was assumed that their population was in decline due to habitat destruction for the creation of pasture and agriculture. Measures of their population density vary widely, from 50 to 550 individuals per square kilometer (250 acres), but these numbers are thought to reflect only small, gum-rich areas, and therefore only small, clustered populations with an overall low population density.[37]

As with all lemurs, fork-marked lemurs were first protected in 1969 when they were listed as "Class A" of the African Convention on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. This prohibited hunting and capture without authorization, which would only be given for scientific purposes or the national interest. They were also protected under CITES Appendix I as of 1973. This strictly regulates their trade and forbids commercial trade. Although enforcement is patchy, they are also protected under Malagasy law. Fork-marked lemurs are rarely kept in captivity,[37] and their captive lifespan can range from 12[61] to 25 years.[62]

References

"Checklist of CITES Species". CITES. UNEP-WCMC. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

Andriaholinirina, N.; et al. (2012). "Phaner furcifer". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

Andriaholinirina, N.; et al. (2012). "Phaner pallescens". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

Andriaholinirina, N.; et al. (2012). "Phaner parienti". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

Andriaholinirina, N.; et al. (2012). "Phaner electromontis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

Mittermeier et al. 2010, pp. 211–212.

Groves 2005, Phaner.

Tattersall 1982, p. 131.

Szalay & Delson 1980, p. 177.

Osman Hill 1953, p. 347.

Masters et al. 2013, pp. 214–215.

Osman Hill 1953, p. 325.

Groves & Tattersall 1991, p. 39.

Groves 2001, p. 71.

Tattersall 2007, p. 16.

"New species of lemur discovered in Madagascar". BBC News. 13 December 2010. Archived from the original on 15 December 2014. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

"New lemur: big feet, long tongue and the size of squirrel" (Press release). Conservation International. 13 December 2010. Archived from the original on 13 December 2014. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

Dunkel, Zijlstra & Groves 2012, pp. 66–67.

Weisrock et al. 2012, p. 1626.

Masters et al. 2013, p. 209.

Chatterjee et al. 2009, p. 5 of 19.

Ankel-Simons 2007, p. 177.

Masters et al. 2013, p. 214.

Masters et al. 2013, pp. 203–204.

Roos, Schmitz & Zischler 2004, p. 10653.

Masters et al. 2013, p. 213.

Tattersall 1982, p. 132.

Mittermeier et al. 2010, pp. 218, 226, & 228.

Tattersall 1982, pp. 131–132.

Fleagle 2013, p. 63.

Charles-Dominique & Petter 1980, p. 84.

Charles-Dominique & Petter 1980, p. 78.

Szalay & Seligsohn 1977, pp. 77–78, & 80.

Swindler 2002, p. 73.

Swindler 2002, pp. 75–76.

Schülke 2003, p. 1320.

Harcourt 1990, pp. 67–69.

Mittermeier et al. 2010, pp. 216–217.

Mittermeier et al. 2010, pp. 228–229.

Mittermeier et al. 2010, pp. 226–227.

Mittermeier et al. 2010, pp. 218–223.

Schülke 2003, p. 1318.

Charles-Dominique & Petter 1980, p. 81.

Schülke 2003, p. 1319.

Nowak 1999, p. 70.

Charles-Dominique & Petter 1980, p. 88.

Charles-Dominique & Petter 1980, pp. 88–90.

Charles-Dominique & Petter 1980, pp. 84–85.

Charles-Dominique & Petter 1980, pp. 81–83.

Charles-Dominique & Petter 1980, pp. 86 & 93.

Charles-Dominique & Petter 1980, pp. 83–84, 86.

Charles-Dominique & Petter 1980, pp. 85–86.

Klopfer & Boskoff 1979, pp. 136–137.

Charles-Dominique & Petter 1980, p. 93.

Charles-Dominique & Petter 1980, p. 77.

Charles-Dominique & Petter 1980, p. 80.

Louis, E. E.; Randriamampoinana, R.; Bailey, C. A.; Sefczek, T. M. (2020). "Phaner furcifer". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

Borgerson, C. (2020). "Phaner pallescens". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

Louis, E. E.; Mittermeier, R. A.; Randrianambinina, B.; Randriatahina, G.; Rasoloharijaona, S.; Wilmet, L.; Ratsimbazafy, J.; Volampeno, S.; Zaonarivelo, J. (2020). "Phaner parienti". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

Sgarlata, G. M.; Le Pors, B.; Salmona, J.; Hending, D.; Chikhi, L.; Cotton, S. (2020). "Phaner electromontis". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

Nowak 1999, p. 71.

Weigl 2005, p. 44.

Literature cited

Ankel-Simons, F. (2007). Primate Anatomy (3rd ed.). Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-372576-9. OCLC 804422748.

Charles-Dominique, P.; Petter, J.J. (1980). "Ecology and social life of Phaner furcifer". In Charles-Dominique, P.; Cooper, H.M.; Hladik, A.; Hladik, C.M.; Pages, E.; Pariente, G.F.; Petter-Rousseaux, A.; Schilling, A.; Petter, J.J. (eds.). Nocturnal Malagasy Primates: Ecology, Physiology, and Behavior. Academic Press. pp. 75–95. ISBN 9780323159715. OCLC 875506676.

Chatterjee, H.J.; Ho, S.Y.W.; Barnes, I.; Groves, C. (2009). "Estimating the phylogeny and divergence times of primates using a supermatrix approach". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 9 (259): 259. Bibcode:2009BMCEE...9..259C. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-9-259. PMC 2774700. PMID 19860891.

Dunkel, A.R.; Zijlstra, J.S.; Groves, C.P. (2012). "Giant rabbits, marmosets, and British comedies: etymology of lemur names, part 1" (PDF). Lemur News. 16: 64–70. ISSN 1608-1439. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-06. Retrieved 2014-12-11.

Fleagle, J.G. (2013). Primate Adaptation and Evolution (3rd ed.). Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-378632-6. OCLC 820107187.

Groves, C. P. (2005). "Order Primates". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

Groves, C.P. (2001). Primate Taxonomy. Smithsonian. ISBN 9781560988724. OCLC 44868886.

Groves, C.P.; Tattersall, I. (1991). "Geographical variation in the fork-marked lemur, Phaner furcifer (Primates, Cheirogaleidae)". Folia Primatologica. 56 (1): 39–49. doi:10.1159/000156526.

Harcourt, C. (1990). Thornback, J (ed.). Lemurs of Madagascar and the Comoros: The IUCN Red Data Book (PDF). World Conservation Union. ISBN 978-2-88032-957-0. OCLC 28425691.

Klopfer, P.H.; Boskoff, K.J. (1979). "Maternal behavior in prosimians". In Doyle, G. A.; Martin, R.D. (eds.). The Study of Prosimian Behavior. Academic Press. pp. 123–157. ISBN 978-0124123915. OCLC 850210233.

Masters, J.C.; Silvestro, D.; Génin, F.; DelPero, M. (2013). "Seeing the wood through the trees: The current state of higher systematics in the Strepsirhini" (PDF). Folia Primatologica. 84 (3–5): 201–219. doi:10.1159/000353179. hdl:2318/140024. PMID 23880733.

Mittermeier, R.A.; Louis, E.E.; Richardson, M.; Schwitzer, C.; et al. (2010). Lemurs of Madagascar. Illustrated by S.D. Nash (3rd ed.). Conservation International. ISBN 978-1-934151-23-5. OCLC 670545286.

Nowak, R.M. (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World (6th ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-8018-5789-8.

Osman Hill, W.C. (1953). Primates Comparative Anatomy and Taxonomy I—Strepsirhini. Edinburgh Univ Pubs Science & Maths, No 3. Edinburgh University Press. OCLC 500576914.

Roos, C.; Schmitz, J.; Zischler, H. (2004). "Primate jumping genes elucidate strepsirrhine phylogeny". PNAS. 101 (29): 10650–10654. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10110650R. doi:10.1073/pnas.0403852101. PMC 489989. PMID 15249661.

Schülke, O. (2003). "Phaner furcifer, Fork-marked Lemur, Vakihandry, Tanta". In Goodman, S.M.; Benstead, J.P. (eds.). The Natural History of Madagascar. University of Chicago Press. pp. 1318–1320. ISBN 978-0-226-30306-2. OCLC 51447871.

Swindler, D.R. (2002). Primate Dentition: An Introduction to the Teeth of Non-human Primates. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139431507. OCLC 70728410.

Szalay, F.S.; Delson, E. (1980). Evolutionary History of the Primates. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0126801507. OCLC 893740473.

Szalay, F.S.; Seligsohn, D. (1977). "Why did the strepsirhine tooth comb evolve?". Folia Primatologica. 27 (1): 75–82. doi:10.1159/000155778. PMID 401757.

Tattersall, I. (1982). The Primates of Madagascar. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-04704-3. OCLC 7837781.

Tattersall, I. (2007). "Madagascar's Lemurs: Cryptic diversity or taxonomic inflation?". Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews. 16 (1): 12–23. doi:10.1002/evan.20126. S2CID 54727842.

Weigl, R. (2005). Longevity of mammals in captivity; from the living collections of the world. Kleine Senckenberg-Reihe. Vol. 48. E. Schweizerbart. ISBN 9783510613793. OCLC 65169976.

Weisrock, D.W.; Smith, S.D.; Chan, L.M.; Biebouw, K.; Kappeler, P.M.; Yoder, A.D. (2012). "Concatenation and concordance in the reconstruction of mouse lemur phylogeny: An empirical demonstration of the effect of allele sampling in phylogenetics". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 29 (6): 1615–1630. doi:10.1093/molbev/mss008. PMC 3351788. PMID 22319174.

Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/"

All text is available under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License