Superregnum: Eukaryota

Cladus: Unikonta

Cladus: Opisthokonta

Cladus: Holozoa

Regnum: Animalia

Subregnum: Eumetazoa

Cladus: Bilateria

Cladus: Nephrozoa

Superphylum: Deuterostomia

Phylum: Chordata

Subphylum: Vertebrata

Infraphylum: Gnathostomata

Megaclassis: Osteichthyes

Cladus: Sarcopterygii

Cladus: Rhipidistia

Cladus: Tetrapodomorpha

Cladus: Eotetrapodiformes

Cladus: Elpistostegalia

Superclassis: Tetrapoda

Cladus: Reptiliomorpha

Cladus: Amniota

Cladus: Synapsida

Cladus: Eupelycosauria

Cladus: Sphenacodontia

Cladus: Sphenacodontoidea

Cladus: Therapsida

Cladus: Theriodontia

Cladus: Cynodontia

Cladus: Eucynodontia

Cladus: Probainognathia

Cladus: Prozostrodontia

Cladus: Mammaliaformes

Classis: Mammalia

Subclassis: Trechnotheria

Infraclassis: Zatheria

Supercohors: Theria

Cohors: Eutheria

Infraclassis: Placentalia

Cladus: Boreoeutheria

Superordo: Laurasiatheria

Cladus: Scrotifera

Ordo: Chiroptera

Subordo: Yangochiroptera

Superfamilia: Noctilionoidea

Familia: Noctilionidae

Genus: Noctilio

Subgenus: Noctilio (Noctilio)

Species: Noctilio leporinus

Subspecies (3): N. l. leporinus – N. l. mastivus – N. l. rufescens

Name

Noctilio leporinus (Linnaeus, 1758)

Holotype: BMNH 1867.4.12.339, adult ♂, body in alcohol, purchased from Lith de Jeude in 1867.

Type locality: “America”, restricted to “Surinam” by Thomas (1911: 131).

Combinations

Vespertilio leporinus Linnaeus, 1758: 32 [original combination]

Noctilio leporinus: Illiger, 1815: 109 [subsequent combination]

Native distribution areas

Noctilio leporinus — distribution map

Mexico (Sinaloa) to the Guianas, South Brazil, North Argentina, Paraguay, Bolivia, and Peru

Trinidad

Greater and Lesser Antilles

South Bahamas: Great Inagua Island

Noctilio leporinus rufescens

References

Primary references

Linnaeus, C. 1758. Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Editio Decima, Reformata. Tomus I. Holmiæ (Stockholm): impensis direct. Laurentii Salvii. 824 pp. DOI: 10.5962/bhl.title.542 BHL Reference page.

Illiger, J.K.W. 1815. Ueberblick der Säugthiere nach ihrer Vertheilung über die Welttheile. Abhandlungen der physikalischen Klasse der Königlich-Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften 1804–1811: 39–140. BHL Reference page.

Thomas, O. 1911. The Mammals of the Tenth Edition of Linnaeus; an Attempt to fix the Types of the Genera and the exact Bases and Localities of the Species. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 81(1): 120–158. DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-7998.1911.tb06995.x BHL Reference page.

Additional references

Thomas, O. 1892. On the probable identity of certain specimens, formerly in the Lidth de Jeude Collection, and now in the British Museum, with those figured by Albert Seba in his ‘Thesaurus’ of 1734. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 60(3): 309–318. DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-7998.1892.tb06833.x Paywall; BHL Reference page.

Davis, W.B. 1973. Geographic Variation in the Fishing Bat, Noctilio leporinus. Journal of Mammalogy 54(4): 862–874. DOI: 10.2307/1379081 Paywall Reference page.

Carter, D.C. & Dolan, P.G. 1978. Catalogue of Type Specimens of Neotropical Bats in Selected European Museums. Special Publications. The Museum Texas Tech University 15: 1–136. BHL Reference page.

Pavan, A.C., Martins, F.M. & Morgante, J.S. 2013. Evolutionary history of bulldog bats (genus Noctilio): recent diversification and the role of the Caribbean in Neotropical biogeography. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 108(1): 210–224. DOI: 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2012.01979.x Open access Reference page.

Pietsch, T.W. & Marx, B. 2021. Charles Plumier's (1646–1704) Vespertilio maximus ex insula Sancti Vincentii: a previously unpublished description and drawings of the Greater Bulldog Bat, Noctilio leporinus (Linnaeus, 1758). Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington 134(1): 29–41. DOI: 10.2988/006-324X-134.1.29 Open access Reference page.

Links

Barquez, R., Perez, S., Miller, B. & Diaz, M. 2015. IUCN: Noctilio leporinus (Least Concern). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T14830A22019554. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T14830A22019554.en. Accessed on 19 June 2024.

Vernacular names

Deutsch: Großes Hasenmaul

English: Greater Bulldog Bat

español: Murciélago pescador grande

français: Grand Noctilion

magyar: Nagy nyúlszájú denevér

italiano: Pipistrello pescatore maggiore

Nederlands: Grote hazenlipvleermuis

português do Brasil: Morcego-pescador-grande

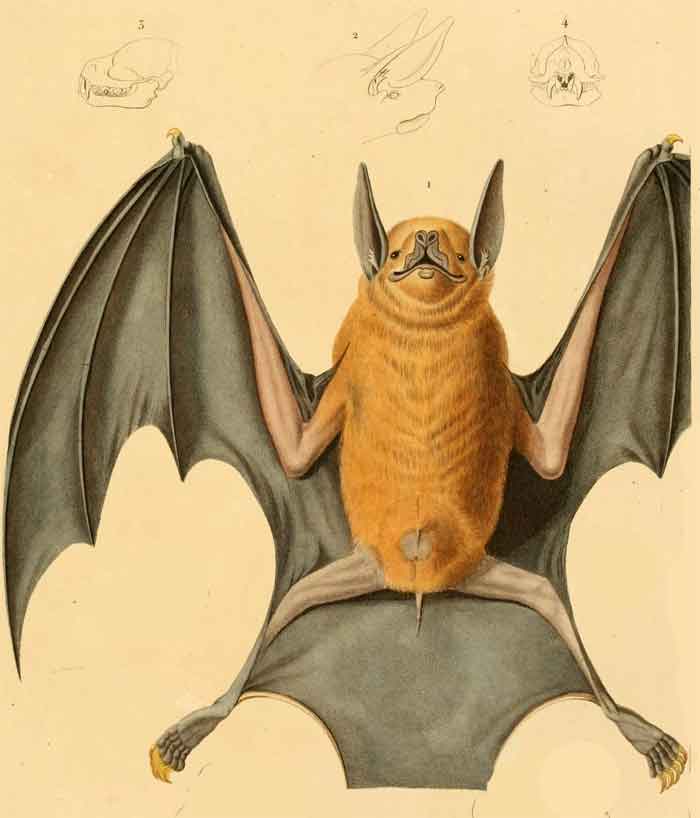

The greater bulldog bat or fisherman bat (Noctilio leporinus) is a species of fishing bat native to Latin America (Spanish: murciélago pescador; Portuguese: morcego-pescador). The bat uses echolocation to detect water ripples made by the fish upon which it preys, then uses the pouch between its legs to scoop the fish up and its sharp claws to catch and cling to it. It is not to be confused with the lesser bulldog bat, which, though belonging to the same genus, merely catches water insects, such as water striders and water beetles.

It emits echolocation sounds through the mouth like Myotis daubentoni, but the sounds are quite different, containing a long constant frequency part around 55 kHz, which is an unusually high frequency for a bat this large.

General description

The greater bulldog bat is a large bat, often with a combined body and head length of 10.9 to 12.7 cm (4.3 to 5.0 in). It generally weighs from 50–90 grams (1.8–3.2 oz).[3] Males tend to be larger than females, with the former averaging 67 grams (2.4 oz) and the latter averaging 56 grams (2.0 oz).[4] They also differ in fur color. Males have bright orange fur on the back while females are dull gray.[5] However, both sexes have pale undersides and may have a pale line that runs down the middle of the back.[5] The males do not have a baculum.[6] The bulldog bat has rounded nostrils that open forward and down. It has elongated, pointed ears with a tragus that gets ridged at the outer edge. The bulldog bat has smooth lips but its upper lip is divided by a skin fold while its bottom lip has a wart above skin folds that extend to the chin.[5] It is these features that give the bulldog bat its name, as it resembles a bulldog.

The bulldog bat has a wingspan of 1 meter (3 feet). The wing of the bat is longer than the head and body combined and 65% of its wingspan is made of the third digit.[7] When in flight, the bat's wings move slowly.[7] This species is a capable swimmer and will use its wings to paddle.[5] The greater bulldog bat also has prominent cheek pouches which are useful for holding its food.[7] Its hind legs and feet are particularly large,[5] capable of 180° rotation when hunting. The leg bones are significantly compressed in order to be streamlined towards the dragging direction.[8]

Distribution and variation

The greater bulldog bat's range stretches from Mexico to Northern Argentina and also includes most Caribbean islands.[7] While vast, its range is also patchy as the bat is limited to mostly well-watered lowland and coastal areas as well as river basins. There is geographical variation in the species and are classified as subspecies. Bats around the Caribbean Basin are large and usually have the pale mid-dorsal stripe, despite varying in pelage.[9] These bats are known as N. l. mastivus. In Guianas and the Amazon Basin, the bats are small and dark and often lack the pale mid-dorsal stripe.[9] These bats are known as N. l. leporinus. In eastern Bolivia, southern Brazil and northern Argentina bats tend to be large and pale, more so than the other subspecies.[9] They are known as N. l. rufenscenes.

Ecology and behavior

The greater bulldog bat lives primarily in tropical lowlands.[10] The bats are commonly found over ponds and streams as well as estuaries and coastal lagoons.[11] They live in colonies that number in the hundreds.[7] In Trinidad, bulldog bats rest in hollow trees like silk-cotton, red mangrove and balatá.[12] The bats live in hollow tree roosts in other areas as well.[7] They also roost in deep sea caves.[12] Like most bats, bulldog bats are nocturnal.

Female bulldog bats stay together in groups while roosting and tend to be accompanied by a resident male. Females associate with the same individuals in the same location for several years unaffected by changes in resident males and movements of the group to different roosts. A male may stay with a female group for two or more reproductive seasons. Bachelor males are segregated from the females and may roost alone or together in small groups. Female bats forage either alone or with their roost mates, with stable female groups continue to forage in the same areas in the long term. Males forage alone and use areas that are larger and separate from those used by the females.[13]

Food and hunting

The greater bulldog bat is one of the few bat species that has adapted to eating fish. Nevertheless, the bats eat both fish and insects. During the wet season, the bats feed primarily on insects like moths and beetles.[3] During the dry season, bats will primarily feed on fish as well as crabs, scorpions and shrimp to a lesser extent.[3] The bulldog bat mostly forages for fish during high tide and locates them with echolocation. A bulldog bat will fly high in the air and in a circular direction when searching for prey. If it spots a jumping fish, the bat will drop down closer to the water surface, particularly the spot where it made the jump, and decreases the pulse duration and intervals of its echolocation signals.[14] The bulldog bat may also search by dragging its feet across the water surface, a behavior known as raking.[14] The bat may rake through areas where fish jumping is most frequent or in areas where it had previously made a successful catch.[14]

Echolocation

Greater bulldog bats emit echolocation signals that are either at constant frequency (CF), frequency-modulated (FM) or a combination of the two (CF-FM).[14] The longest signals are the pure CF signal which typically last 13.3 ms but can go as long as 17 ms.[14] CF-FM signals have CF followed by an FM. In a CF-FM signal, the CF are typically 8.9 ms with a frequency of 52.8–56.2 kHz while the FM ranges up to 3.9 ms with 25.9 kHz bandwidth.[14] Bulldog bats have two kinds of signal when flying. In one, the CF pulses begin at 60 kHz of frequency and may fall no further than 50 kHz.[7] The second type has the CF starting at a frequency of 60 kHz and then falls for more than a single octave.[7]

Reproduction

For females, pregnancy occurs from September until January, and lactation starts in November and continues until April.[5] Only one young is born each gestation.[7] Male bats mostly breed autumn and winter.[7] Young bats stay in the roosts for one month and are then capable of flight.[7] Both the male and female care for the young.[7]

Status

While the bulldog bat is not in danger overall, the bat is nevertheless threatened by water pollution, persecution, changing water levels, cave disturbances, and deforestation.[1]

References

Barquez, R.; Perez, S.; Miller, B.; Diaz, M. (2015). "Noctilio leporinus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T14830A22019554. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T14830A22019554.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

Linnæus, Carl (1758). Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I (in Latin) (10th ed.). Holmiæ: Laurentius Salvius. p. 32. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

Brooke, A. (1994). "Diet of the Fishing Bat, Noctilio Leporinus (Chiroptera: Noctilionidae)". Journal of Mammalogy. 75 (1): 212–219. doi:10.2307/1382253. JSTOR 1382253.

Eisenburg, J. (1989) Mammals of the Neotropics. University of Chicago Press.

Nowak, R. (1999) Bulldog Bats, or Fisherman Bats. Walker’s Mammals of the World. 6ed: 347–349.

Elizabeth G. Crichton; Philip H. Krutzsch (12 June 2000). Reproductive Biology of Bats. Academic Press. pp. 94–. ISBN 978-0-08-054053-5.

Hood, C. S.; Jones, J. K. (1984). "Noctilio leporinus" (PDF). Mammalian Species (216): 1–7. doi:10.2307/3503809. JSTOR 3503809. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-12-05. Retrieved 2011-02-28.

Vaughan, Terry A. (1978). Mammalogy. W.B. Saunders Company. ISBN 0-7216-9009-2.

Davis, William B. (1973). "Geographic Variation in the Fishing Bat, Noctilio leporinus". Journal of Mammalogy. 54 (4): 862–874. doi:10.2307/1379081. JSTOR 1379081.

Larry C. Watkins, J. Knox Jones, Hugh H. Genoways, (1972) Bats of Jalisco Mexico, Museum of Texas Tech Univ, 1:1–44. ISBN 978-0-89672-026-8

Smith, J. D.; Genoways, H. H. (1974). "Bats of Margarita Island, Venezuela, with zoogeographic comments". Bulletin of the Southern California Academy of Sciences. 73: 64–79.

Goodwin, C.G.; Greenhall, A. (1961). "A review of the bats of Trinidad and Tobago". Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 122: 187–302. hdl:2246/1270.

Brooke, A. May (1997). "Organization and Foraging Behaviour of the Fishing Bat, Noctilio leporinus (Chiroptera:Noctilionidae)". Ethology. 103 (5): 421–436. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1997.tb00157.x.

Schnitzler, Hans-Ulrich; Kalko, Elisabeth K. V.; Kaipf, Ingrid; Grinnell, Alan D. (1994). "Fishing and Echolocation Behavior of the Greater Bulldog Bat, Noctilio leporinus, in the Field". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 35 (5): 327–345. doi:10.1007/BF00184422. S2CID 23782948.

Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/"

All text is available under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License