Superregnum: Eukaryota

Cladus: Unikonta

Cladus: Opisthokonta

Cladus: Holozoa

Regnum: Animalia

Subregnum: Eumetazoa

Cladus: Bilateria

Cladus: Nephrozoa

Superphylum: Deuterostomia

Phylum: Chordata

Subphylum: Vertebrata

Infraphylum: Gnathostomata

Megaclassis: Osteichthyes

Cladus: Sarcopterygii

Cladus: Rhipidistia

Cladus: Tetrapodomorpha

Cladus: Eotetrapodiformes

Cladus: Elpistostegalia

Superclassis: Tetrapoda

Cladus: Reptiliomorpha

Cladus: Amniota

Cladus: Synapsida

Cladus: Eupelycosauria

Cladus: Sphenacodontia

Cladus: Sphenacodontoidea

Cladus: Therapsida

Cladus: Theriodontia

Cladus: Cynodontia

Cladus: Eucynodontia

Cladus: Probainognathia

Cladus: Prozostrodontia

Cladus: Mammaliaformes

Classis: Mammalia

Subclassis: Trechnotheria

Infraclassis: Zatheria

Supercohors: Theria

Cohors: Eutheria

Infraclassis: Placentalia

Cladus: Boreoeutheria

Superordo: Laurasiatheria

Cladus: Scrotifera

Cladus: Ferungulata

Cladus: Euungulata

Ordo: Artiodactyla

Cladus: Artiofabula

Cladus: Cetruminantia

Subordo: Ruminantia

Cladus: Pecora

Superfamilia: Bovoidea

Familia: Moschidae

Genus: Moschus

Species (7): M. anhuiensis – M. berezovskii – M. chrysogaster – M. cupreus – M. fuscus – M. leucogaster – M. moschiferus

Name

Moschus Linnaeus, 1758: 66 [conserved name]

Type species: Moschus moschiferus Linnaeus, 1758, by monotypy.

Gender: masculine.

Placed on the Official List of Generic Names in Zoology by Opinion 75 (1922: 37).

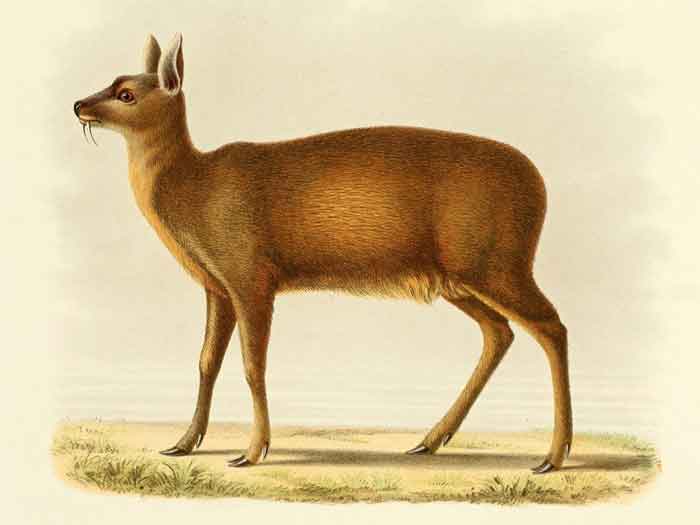

Moschus chrysogaster

References

Primary references

Linnaeus, C. 1758. Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Editio Decima, Reformata. Tomus I. Holmiæ (Stockholm): impensis direct. Laurentii Salvii. 824 pp. DOI: 10.5962/bhl.title.542 BHL Reference page.

International Commisision on Zoological Nomenclature 1922. Opinion 75. Twenty-seven generic names of Protozoa, Vermes, Pisces, Reptilia and Mammalia included in the Official List of Zoological Names. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 73(1): 35–37. BHL Reference page.

Vernacular names

Deutsch: Moschushirsche

Ελληνικά: Μόσχος

English: Musk Deer

suomi: Myskihirvet

français: Cerfs Porte-musc

한국어: 사향노루속

português: Cervo-almiscarado

ไทย: กวางชะมด

Türkçe: Misk geyiğigiller

Musk deer can refer to any one, or all eight, of the species that make up Moschus, the only extant genus of the family Moschidae.[1] Despite being commonly called deer, they are not true deer belonging to the family Cervidae, but rather their family is closely related to Bovidae, the group that contains antelopes, bovines, sheep, and goats. The musk deer family differs from cervids, or true deer, by lacking antlers and preorbital glands also, possessing only a single pair of teats, a gallbladder,[2] a caudal gland, a pair of canine tusks and—of particular economic importance to humans—a musk gland.

Musk deer live mainly in forested and alpine scrub habitats in the mountains of South Asia, notably the Himalayas. Moschids, the proper term when referring to this type of deer rather than one/multiple species of musk deer, are entirely Asian in their present distribution, being extinct in Europe where the earliest musk deer are known to have existed from Oligocene deposits.

Characteristics

Skull of a buck showing the characteristic teeth

Musk deer resemble small deer, with a stocky build and hind legs longer than their front legs. They are about 80 to 100 cm (31 to 39 in) long, 50 to 70 cm (20 to 28 in) high at the shoulder, and weigh between 7 and 17 kg (15 and 37 lb). The feet of musk deer are adapted for climbing in rough terrain. Like the Chinese water deer, a cervid, they have no antlers, but the males do have enlarged upper canines, forming sabre-like tusks. The dental formula is similar to that of true deer: 0.1.3.33.1.3.3

The musk gland is found only in adult males. It lies in a sac located between the genitals and the umbilicus, and its secretions are most likely used to attract mates.

Musk deer are herbivores, living in hilly, forested environments, generally far from human habitation. Like true deer, they eat mainly leaves, flowers, and grasses, with some mosses and lichens. They are solitary animals and maintain well-defined territories, which they scent mark with their caudal glands. Musk deer are generally shy and either nocturnal or crepuscular.

Males leave their territories during the rutting season and compete for mates, using their tusks as weapons. In order to indicate their area, musk deer build latrines. These locations can be used to identify the musk deer's existence, number, and preferred habitat in the wild.[citation needed] Female musk deer give birth to a single fawn after about 150–180 days. The newborn young are very small and essentially motionless for the first month of their lives, a feature that helps them remain hidden from predators.[3]

Musk deer have been hunted for their scent glands, which are used in perfumes. The glands can fetch up to $45,000/kg on the black market.[clarification needed] It is rumored that ancient royalty wore the scent of the musk deer, and that it is an aphrodisiac.[4]

Population

Musk deer have a global population between 400,000 to 800,000 currently, however the exact count is undetermined.[5] They are widely spread; however, their population density increases within China, Russia, and Mongolia. Musk deer are commonly found in China, and they are spread over 17 provinces.[6][7][8] This population is mainly located around the Himalayas in southern Asia, southeast Asia, and eastern Asia.[7] They are also found in a few spots in Russia. As of 2003, they became a protected species due to their declined overall population.[6] Musk deer have many subspecies that have varying population sizes, within the overall total, and all are threatened.[6] Over the past twenty years, the populations are being able to slightly recover due to the captive breeding of these animals, specifically in China.[8] Musk deer populations are recovering due to the protocols and rules being set in place to protect the species.[8]

Habitat

The musk deer species is generally solitary and lives in the higher regions of mountain ranges, such as the Himalayas. The varying species' habitats include different atmospheres and necessary resources for their survival, while including similar universal resources. Musk deer population has been declining recently due to environmental and human factors.[5] As a large-bodied mammal, they have great needs that are not able to be sustained due to habitat fragmentation.[9] This species is largely protected due to the threat of extinction, due to the increase in illegal hunting. Illegal hunting has significantly decreased the population throughout many of the provinces musk deer occupy.[8] Their habitats are being lost to colonization and deforestation and hunting for musk deer was on the rise.[6] They were hunted for their distinct products that are very valuable in the market.[7] Since then, the Chinese government has stepped in to regulate these issues.[6] They have placed rules pertaining to the killing of musk deer and created havens for the deer to survive. To help with the declining numbers, the deforestation of their natural habitat should be stopped and new habitats should be invested in them.[5] Global climate change has also driven the musk deer population down. The warmer climates result in the drive to higher elevations and latitudes.[10] Global warming and habitat fragmentation are two causes for the population decrease.

Evolution

Skeleton of Micromeryx showing the general skeletal features

Musk deer are the only surviving members of the Moschidae, a family with a fossil record extending over 25 million years to the late Oligocene. The group was abundant across Eurasia and North America until the late Miocene, but underwent a substantial decline, with no Pliocene fossil record and Moschus the only genus since the Pleistocene. The oldest records of the genus Moschus are known from the Late Miocene (Turolian) of Lufeng, China.[11]

Taxonomy

For a complete taxonomy, see Moschidae.

While they have been traditionally classified as members of the deer family (as the subfamily "Moschinae") and all the species were classified as one species (under Moschus moschiferus), recent studies have indicated that moschids are more closely related to bovids (antelope, goats, sheep and cattle).[12][13]

Genus Moschus

| Species name | Common name | Distribution |

|---|---|---|

| M. moschiferus | Siberian musk deer | North East Asia |

| M. anhuiensis | Anhui musk deer | Eastern China |

| M. berezovskii | Dwarf musk deer | South China and Northern Vietnam |

| M. fuscus | Black musk deer | Eastern Himalayas |

| M. chrysogaster | Alpine musk deer | Eastern Himalayas |

| M. cupreus | Kashmir musk deer | Western Himalayas and Hindu Kush |

| M. leucogaster | White-bellied musk deer | Central Himalayas |

See also

Vampire deer

References

"Moschus (musk deer) Classification". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology.

"On the structure and affinities of the musk-deer (Moschus mosciferus, Linn.)". 1875.

Frädrich H (1984). "Deer". In Macdonald D (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York: Facts on File. pp. 518–9. ISBN 978-0-87196-871-5.

Wild Russia, Discovery Channel[full citation needed]

Green, Michael J.B. (1986). "The distribution, status and conservation of the Himalayan musk deer Moschus chrysogaster". Biological Conservation. 35 (4): 347–375. Bibcode:1986BCons..35..347G. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(86)90094-7.

Meng, X; Yang, Q (March 2003). "Conservation status and causes of decline of musk deer (Moschus spp.) in China". Biological Conservation. 109 (3): 333–342. Bibcode:2003BCons.109..333Y. doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(02)00159-3.

Zhou, Yijun; Meng, Xiuxiang; Feng, Jinchao; Yang, Qisen; Feng, Zuojian; Xia, Lin; Bartoš, Luděk (June 8, 2004). "Review of the distribution, status and conservation of musk deer in China". Folia Zoologica-Praha. 53 (2): 129–140.

Liu, Gang; Zhang, Bao-Feng; Chang, Jiang; Hu, Xiao-Long; Li, Chao; Xu, Tin-Tao; Liu, Shu-Qiang; Hu, De-Fu (2022-09-23). "Population genomics reveals moderate genetic differentiation between populations of endangered Forest Musk Deer located in Shaanxi and Sichuan". BMC Genomics. 23 (1): 668. doi:10.1186/s12864-022-08896-9. ISSN 1471-2164. PMC 9503231. PMID 36138352.

Zhixiao, Liu; Helin, Sheng (2002-03-01). "Effect of Habitat Fragmentation and Isolation on the Population of Alpine Musk Deer". Russian Journal of Ecology. 33 (2): 121–124. doi:10.1023/A:1014456909480. ISSN 1608-3334.

Jiang, Feng; Zhang, Jingjie; Gao, Hongmei; Cai, Zhenyuan; Zhou, Xiaowen; Li, Shengqing; Zhang, Tongzuo (February 2020). "Musk deer (Moschus spp.) face redistribution to higher elevations and latitudes under climate change in China". Science of the Total Environment. 704: 135335. Bibcode:2020ScTEn.70435335J. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135335. ISSN 0048-9697. PMID 31784177.

G. Qi. 1985. Stratigraphic summarization of Ramapithecus fossil locality, Lufeng, Yunnan. Acta Anthropologica Sinica (Renleixue xuebao) 4(1): 55–69

Hassanin A, Douzery EJ (April 2003). "Molecular and morphological phylogenies of ruminantia and the alternative position of the moschidae". Systematic Biology. 52 (2): 206–28. doi:10.1080/10635150390192726. PMID 12746147.

Guha S, Goyal SP, Kashyap VK (March 2007). "Molecular phylogeny of musk deer: a genomic view with mitochondrial 16S rRNA and cytochrome b gene". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 42 (3): 585–97. Bibcode:2007MolPE..42..585G. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.06.020. PMID 17158073.

Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/"

All text is available under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License