Geomys bursarius

Superregnum: Eukaryota

Cladus: Unikonta

Cladus: Opisthokonta

Cladus: Holozoa

Regnum: Animalia

Subregnum: Eumetazoa

Cladus: Bilateria

Cladus: Nephrozoa

Superphylum: Deuterostomia

Phylum: Chordata

Subphylum: Vertebrata

Infraphylum: Gnathostomata

Megaclassis: Osteichthyes

Cladus: Sarcopterygii

Cladus: Rhipidistia

Cladus: Tetrapodomorpha

Cladus: Eotetrapodiformes

Cladus: Elpistostegalia

Superclassis: Tetrapoda

Cladus: Reptiliomorpha

Cladus: Amniota

Cladus: Synapsida

Cladus: Eupelycosauria

Cladus: Sphenacodontia

Cladus: Sphenacodontoidea

Cladus: Therapsida

Cladus: Theriodontia

Cladus: Cynodontia

Cladus: Eucynodontia

Cladus: Probainognathia

Cladus: Prozostrodontia

Cladus: Mammaliaformes

Classis: Mammalia

Subclassis: Trechnotheria

Infraclassis: Zatheria

Supercohors: Theria

Cohors: Eutheria

Infraclassis: Placentalia

Cladus: Boreoeutheria

Superordo: Euarchontoglires

Ordo: Rodentiaa

Subordo: Castorimorpha

Familia: Geomyidae

Genus: Geomys

Species: Geomys bursarius

Subspecies: G. b. bursarius – G. b. illinoensis – G. b. industrius – G. b. jugossicularis – G. b. lutescens – G. b. major – G. b. majusculus – G. b. missouriensis – G. b. ozarkensis – G. b. wisconsinensis

Name

Geomys bursarius (Shaw, 1800)

References

Geomys bursarius in Mammal Species of the World.

Wilson, Don E. & Reeder, DeeAnn M. (Editors) 2005. Mammal Species of the World – A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. Third edition. ISBN 0-8018-8221-4.

IUCN: Geomys bursarius (Shaw, 1800) (Least Concern)

Links

North American Mammals: Geomys bursarius [1]

Vernacular names

čeština: Pytlonoš nížinný

English: Plains Pocket Gopher

polski: Goffer

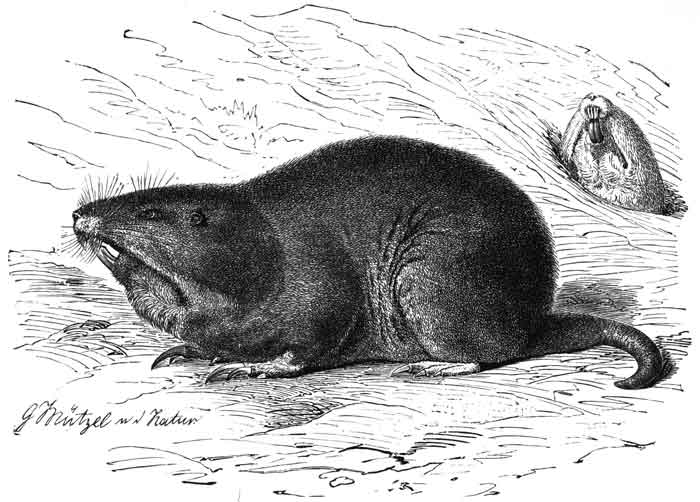

The plains pocket gopher (Geomys bursarius) is one of 35 species of pocket gophers, so named in reference to their externally located, fur-lined cheek pouches. They are burrowing animals, found in grasslands and agricultural land across the Great Plains of North America, from Manitoba to Texas. Pocket gophers are the most highly fossorial rodents found in North America.[2]

Distribution

Plains pocket gophers are found throughout the Great Plains of North America, ranging from southern Manitoba (Canada), and eastern North Dakota south to New Mexico and Texas in the United States, and as far east as the extreme western parts of Indiana. Eight subspecies are currently recognised, although some former subspecies have since been considered to be species in their own right, and are no longer included:[3]

Geomys bursarius bursarius – Canada, the Dakotas, Minnesota

Geomys bursarius illinoensis – Illinois

Geomys bursarius industrius – southwestern Kansas

Geomys bursarius major – Texas, Oklahoma, eastern New Mexico

Geomys bursarius majusculus – Iowa, eastern Nebraska and Kansas, northern Missouri

Geomys bursarius missouriensis – eastern Missouri

Geomys bursarius ozarkensis – Arkansas

Geomys bursarius wisconsinensis – western Wisconsin

Fossil remains have been found as far south as Tennessee, indicating a late Pleistocene, early Holocene population. This would support the hypothesis that drier environmental conditions with extensive prairies extended further south during the Late Wisconsinan glacial period, supporting populations of Geomys and other prairie species such as thirteen-lined ground squirrels and prairie chickens.[4]

Description

G. bursarius has short fur with brown to black coloration over the upper body and lighter brown or tan fur on the underparts. Whitish hairs cover the tops of the feet, while the short, tapered tail is nearly naked. Fossorial adaptations include small eyes, short, naked ears, and large fore feet with heavy claws. Zygomatic arches are widely flared, providing ample room for muscle attachment,[5] although, unlike other pocket gophers, this species does not use the curved incisors to assist the feet in digging.[3] The external cheek pouches, which distinguish this family from other mammals, can be turned inside-out for grooming purposes. They are used for carrying food up to 7 cm (2.8 in) in length and have a forward opening.[6]

Other adaptations to a fossorial lifestyle include a low resting metabolic rate of 0.946 ml O2/g/h,[3] and high conductance, a tolerance for low oxygen levels and high carbon dioxide levels, and a decreased water intake.[7]

Males are significantly larger than females, with a total body length of 25 to 35 cm (9.8 to 13.8 in), compared with 21 to 32 cm (8.3 to 12.6 in) in females. The tail is short and hairless, reaching 5 to 11 cm (2.0 to 4.3 in) in length, and only marginally longer in males. Adults males weigh from 230 to 473 g (8.1 to 16.7 oz) and females 128 to 380 g (4.5 to 13.4 oz).[3]

Ecology

Plains pocket gophers prefer deep, sandy, friable soils to facilitate their burrowing lifestyle and their herbivorous diet of plant roots. The local vegetation is less significant than the nature of the soil, and the gophers are found in prairie grasslands, agricultural land, and even urban areas.[8]

A long-term controlled study of tunnel excavation by plains pocket gophers found that the rate of tunnel construction ranges from a high of 2,059 cm/week of new tunnels to a low of none over several weeks during the summer. About 30 to 50 m (98 to 164 ft) of tunnels were open at any one time. Factors affecting the size of the tunnel system appeared to be influenced more by the amount of energy needed to maintain and patrol it rather than the amount of vegetation present.[9] Tunnels include nests, located about 50 cm (20 in) under ground, and lined with grass and other plant material, as well as food caches containing grasses, roots, and tubers.[3]

The gophers share their tunnels with numerous species of insects, including flies, scarab[10] and carrion beetles,[11] and cave crickets.[12] Known predators include rattlesnakes, prairie kingsnakes, gopher snakes, feral cats, coyotes, foxes, badgers, hawks, and owls.[3]

Behavior

Plains pocket gophers show no seasonal change in activity, except for an increased level of activity during mating season. They do show a bimodal pattern of activity during the day with increased activity occurring from 1300–1700 and then again from 2200–0600.[7] For a fossorial animal with a metabolically expensive lifestyle (360–3400 times as much as terrestrial creatures), planning daily activity around burrow temperature, where lack of air flow and high humidity lead to a decrease in evaporative and convective cooling, is likely to be important.[2]

The gophers spend 72% of their time in their nests, coming above ground to search for food or mates, and for young animals to establish new burrows. Territorial and aggressive, especially in male-to-male interaction, these rodents appear to use their greatly increased sensitivity to soil vibration to maintain their solitary lifestyle. They rarely explore burrows inhabited by other gophers, although they sometimes investigate those that have been previously abandoned.[3]

Reproduction

Plains pocket gophers typically breed only once a year, although they may sometimes breed twice in good years or warmer climates. The breeding season varies with latitude, ranging from April to May in Wisconsin to as long as January to September in Texas. Females give birth to one to six young after a gestation period around 30 days.[3] However, pregnancies lasting up to 51 days have been recorded, and this variation may indicate some form of delayed fertilization, delayed implantation, or delayed zygote development.[citation needed]

The young are born hairless and blind, and initially weigh about 5 g (0.18 oz). They begin to develop fur at 10 days, open their eyes at three weeks, and are weaned by five weeks of age. Although they initially move around in their mother's burrow, after weaning, they quickly leave to establish burrows of their own, and reach the full adult size after about three months.[3]

Conservation

Due to the widespread distribution of this species, its adaptability to suitable habitat, the lack of any major threats, and an apparently stable population, G. bursarius has a conservation status of Least Concern.[1] Though pocket gophers are considered to be no more than pests by farmers and suburban lawn owners, they play active roles in soil aeration, flood control via improved drainage, and soil and plant diversity.[5][13]

References

Cassola, F. (2017) [errata version of 2016 assessment]. "Geomys bursarius". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T42588A115192675. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T42588A22217794.en. Retrieved 17 May 2023. Database entry includes a brief justification of why this species is of least concern

Vaughan, Terry A. et al. (2000) Mammalogy, 4th Edition. Thomson Learning, Inc.

Connior, M.B. (2011). "Geomys bursarius (Rodentia: Geomyidae)". Mammalian Species. 43 (1): 104–117. doi:10.1644/879.1.

Sullivan, R. M. (1981). "A late Pleistocene population of the pocket gopher, Geomys cf. bursarius, in the Nashville Basin, Tennessee". Journal of Mammalogy. 62 (4): 831–835. doi:10.2307/1380607. JSTOR 1380607.

Teeter, K. (2000) Geomys bursarius. Animal Diversity Web.

Kurta, Allen (1995). Mammals of the Great Lakes Region, Revised Edition. The University of Michigan Press.

Benedix Jr., J. H. (1994). "A predictable pattern of daily activity by pocket gopher Geomys bursarius". Animal Behaviour. 48 (3): 501–509. doi:10.1006/anbe.1994.1271. S2CID 54429471.

Pitts, R.M. & Choate, J.R. (1007). "Reproduction of the plains pocket gopher (Geomys bursarius) in Missouri". Southwestern Naturalist. 42 (2): 238–240. JSTOR 30055269.

Thorne, D.H. & Andersen, D.C. (1990). "Long-term soil-disturbance pattern by a pocket gopher, Geomys bursarius". Journal of Mammalogy. 71 (1): 84–89. doi:10.2307/1381322. JSTOR 1381322.

Gordon, R. D. and Skelley, P. E. (2007). "A monograph of the Aphodiini inhabiting the United States and Canada (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae: Aphodiinae)". Memoirs of the American Entomological Institute, Vol. 79. The American Entomological Institute, Gainesville, Florida.

Peck. S.B. & Skelley, P.E. (2001). "Small carrion beetles (Coleoptera: Leiodidae: Cholevinae) from burrows of Geomys and Thomomys pocket gophers (Rodentia: Geomyidae) in the United States". Insecta Mundi. 15 (3): 139–148. Archived from the original on 2017-07-30. Retrieved 2011-08-21.

Kavorik, P.; et al. (2001). "Insects inhabiting the burrows of the Ozark pocket gopher in Arkansas" (PDF). Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science. 62: 75–78.

Reichman, O.J.; et al. (2002). "The role of pocket gophers as subterranean ecosystem engineers". Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 17: 44–49. doi:10.1016/s0169-5347(01)02329-1.

Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/"

All text is available under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License