Bassaricyon gabbii (*)

Superregnum: Eukaryota

Cladus: Unikonta

Cladus: Opisthokonta

Cladus: Holozoa

Regnum: Animalia

Subregnum: Eumetazoa

Cladus: Bilateria

Cladus: Nephrozoa

Superphylum: Deuterostomia

Phylum: Chordata

Subphylum: Vertebrata

Infraphylum: Gnathostomata

Megaclassis: Osteichthyes

Cladus: Sarcopterygii

Cladus: Rhipidistia

Cladus: Tetrapodomorpha

Cladus: Eotetrapodiformes

Cladus: Elpistostegalia

Superclassis: Tetrapoda

Cladus: Reptiliomorpha

Cladus: Amniota

Cladus: Synapsida

Cladus: Eupelycosauria

Cladus: Sphenacodontia

Cladus: Sphenacodontoidea

Cladus: Therapsida

Cladus: Theriodontia

Subordo: Cynodontia

Infraordo: Eucynodontia

Cladus: Probainognathia

Cladus: Prozostrodontia

Cladus: Mammaliaformes

Classis: Mammalia

Subclassis: Trechnotheria

Infraclassis: Zatheria

Supercohors: Theria

Cohors: Eutheria

Infraclassis: Placentalia

Cladus: Boreoeutheria

Superordo: Laurasiatheria

Cladus: Ferae

Ordo: Carnivora

Subordo: Caniformia

Infraordo: Arctoidea

Superfamilia: Musteloidea

Familia: Procyonidae

Subfamilia: Potosinae

Genus: Bassaricyon

Species: Bassaricyon gabbii

Name

Bassaricyon gabbii J.A.Allen, 1876

Vernacular names

Deutsch: Mittelamerika-Makibär

English: Bushy-tailed Olingo

magyar: Ecsetfarkú nyestmedve

Nederlands: Gabbi's slankbeer

polski: Olingo puszystoogonowy

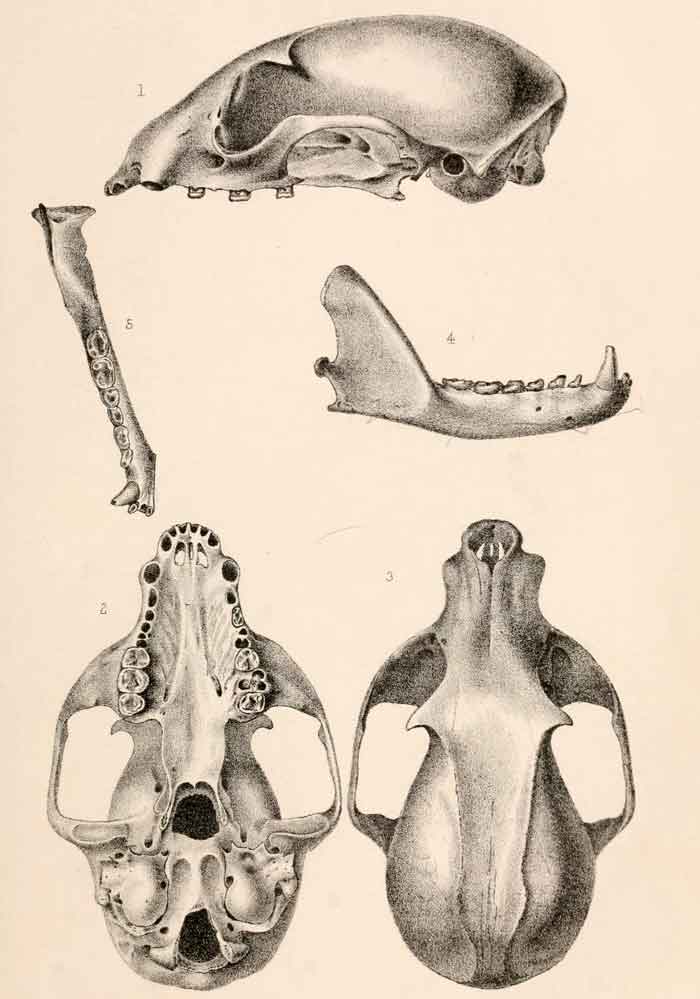

The northern olingo (Bassaricyon gabbii), also known as the bushy-tailed olingo or as simply the olingo (due to it being the most commonly seen of the species),[2] is a tree-dwelling member of the family Procyonidae, which also includes raccoons. It was the first species of olingo to be described, and while it is considered by some authors to be the only genuine olingo species,[3] a recent review of the genus Bassaricyon has shown that there are a total of four olingo species, although two of the former species should now be considered as a part of this species.[2] Its scientific name honors William More Gabb, who collected the first specimen.[4][5] It is native to Central America.[2]

Description

The northern olingo is a slender arboreal animal, with hind legs distinctly longer than the fore legs, and a long, bushy tail. The face is short and rounded, with relatively large eyes and short round ears.[6] The fur is thick and colored brown or grey-brown over most of the body, becoming slightly darker along the middle of the back, while the underparts are light cream to yellowish.[6] A band of yellowish fur runs around the throat and sides of the head, where it reaches the base of the ears, while the face has greyish fur. The tail is similar in color to the body, but has a number of faint rings of darker fur along its length. The soles of the feet are hairy, and the toes are slightly flattened, ending with short, curved claws.[6] Females have a single pair of teats, located on the rear part of the abdomen, close to the hind legs.[4]

Adults have a head-body length of 36 to 42 centimetres (14 to 17 in), with a 38 to 48 centimetres (15 to 19 in) tail.[6] They weigh around 1.2 to 1.4 kilograms (2.6 to 3.1 lb).[6] The northern olingo possesses a pair of anal scent glands,[6] capable of producing a foul-smelling chemical when the animal is alarmed.[4]

This is the largest of the olingo species.[2] Its pelage is typically less rufous than the other olingos, while its tail bands are a bit more distinct.[2]

Distribution and habitat

The northern olingo is found from Nicaragua through Costa Rica and western Panama.[2] It has also been reported from Honduras and Guatemala, although its great similarity to other olingos, and to kinkajous, may make such reports suspect, and they are not currently recognised by the IUCN.[1] While some individuals have been found as low as sea level,[2] it typically inhabits montane[2] and tropical moist forests[4] from 1,000 metres (3,300 ft)[2] up to around 2,000 metres (6,600 ft) elevation, although it apparently avoids plantations and areas of secondary forest.[4]

Taxonomy

Previously, three subspecies (including the nominate) were recognized of this olingo: B. g. gabbii, B. g. richardsoni, and B. g. medius.[3] The recent review of the genus has made several changes to the definition of this species:

The Nicaraguan population B. g. richardsoni may truly be a subspecies, but further review and analysis is needed.[2]

B. g. medius is smaller on average than Bassaricyon gabbii and the morphologic and genetic analysis demonstrated that is a different species: B. medius (western lowland olingo).[2]

Former species B. lasius and B. pauli have been demoted into synonyms for B. gabbii, but may be elevated to subspecies as B. g. lasius and B. g. pauli.[2]

The closest relatives of B. gabbii are the two lowland olingo species of Panama and northwestern South America, B. alleni and B. medius, from which it diverged about 1.8 million years ago.[2]

Diet and behavior

The northern olingo is a nocturnal herbivore, feeding almost entirely on fruit, especially figs. It has been observed to drink the nectar of balsa trees during the dry season, and, on rare occasions, to pursue and eat small mammals, such as mice and squirrels. During the day, it sleeps in dens located in large trees.[4] It has an estimated home range of around 23 hectares (57 acres).[7]

Although it has been considered to be a solitary animal, it is often encountered in pairs, and may be more sociable than commonly believed. It is arboreal, spending much of its time in trees. Its tail is not prehensile, unlike that of the related kinkajous, although it can act as a balance.[4] The call of the northern olingo has been described as possessing two distinct notes, with a "whey-chuck" or "wey-toll" sound.[7]

The northern olingo has a diet and habitat similar to those of kinkajous, and, when resources are in short supply, the larger animal may drive it away from its preferred trees.[7] Predators known to feed on the northern olingo include the jaguarundi, ocelot, tayra, and several boas. It is believed to breed during the dry season, and to give birth to a single young after a gestation period of around ten weeks. It has lived for up to twenty-five years in captivity.[4]

References

Helgen, K.; Kays, R.; Pinto, C.; González-Maya, J.F.; Schipper, J. (2016). "Bassaricyon gabbii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T48637946A45196211. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T48637946A45196211.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

Helgen, K. M.; Pinto, M.; Kays, R.; Helgen, L.; Tsuchiya, M.; Quinn, A.; Wilson, D.; Maldonado, J. (15 August 2013). "Taxonomic revision of the olingos (Bassaricyon), with description of a new species, the Olinguito". ZooKeys (324): 1–83. doi:10.3897/zookeys.324.5827. PMC 3760134. PMID 24003317.

Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 532–628. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

Prange, S. & Prange, T.J. (2009). "Bassaricyon gabbii (Carnivora: Procyonidae)". Mammalian Species. 826: 1–7. doi:10.1644/826.1.

Beolens, B.; Watkins, M.; Grayson, M. (2009-09-28). The Eponym Dictionary of Mammals. The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-0801893049. OCLC 270129903.

Saavedra-Rodriguez, Carlos Arturo; Velandia-Perilla, Jorge H. "Bassaricyon gabbii Allen, 1876 (Carnivora: Procyonida): New distribution point on western range of Colombian Andes". Check List: 505–507.

Kays, R.W. (2000). "The behavior and ecology of olingos (Bassaricyon gabbii) and their competition with kinkajous (Potos flavus) in central Panama" (PDF). Mammalia. 64 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1515/mamm.2000.64.1.1. S2CID 84467601.[dead link]

Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/"

All text is available under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License