Callorhinus ursinus (NOAA National Marine Mammal Laboratory)

Superregnum: Eukaryota

Cladus: Opisthokonta

Regnum: Animalia

Subregnum: Eumetazoa

Cladus: Bilateria

Cladus: Nephrozoa

Cladus: Deuterostomia

Phylum: Chordata

Subphylum: Vertebrata

Infraphylum: Gnathostomata

Superclassis: Tetrapoda

Classis: Mammalia

Subclassis: Theria

Infraclassis: Placentalia

Ordo: Carnivora

Subordo: Caniformia

Familia: Otariidae

Subfamilia: Arctocephalinae

Genus: Callorhinus

Species: Callorhinus ursinus

Name

Callorhinus ursinus (Linnaeus, 1758)

Type locality: "in Camschatcæ maritimus inter Asiam and Americam proximam, primario in infula Beringri," restricted by Thomas (1911a) to "Bering Island."

Synonyms

* Callorhinus alascanus (Jordan & Clark, 1898)

* Callorhinus californianus (Gray, 1866)

* Callorhinus curilensis (Jordan & Clark, 1899)

* Callorhinus krachenninikowii (Lesson, 1828)

* Callorhinus mimica (Tilesius, 1835)

* Callorhinus nigra (Pallas, 1811)

* Siren cynocephala Walbaum, 1792

References

* Linnaeus, C. 1758. Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classis, ordines, genera species cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tenth Edition (10 ed.), Laurentii Salvii, Stockholm, 1: 37

* Gray, J. E. 1866. Notes on the skulls of sea bears and sea lions (Otariidae) in the British Museum. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 18: 228–237.

* Lesson, R.-P. 1828. Phoque. Pp. 400–426 in Dictionaire classique d’histoire naturelle (J. G. B. M. Bory de Saint-Vincent, ed.). Rey et Gravier, Paris, France.

Links

* Callorhinus ursinus on Mammal Species of the World.

* Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 2 Volume Set edited by Don E. Wilson, DeeAnn M. Reeder

* IUCN link: Callorhinus ursinus (Linnaeus, 1758) (Vulnerable)

* Callorhinus ursinus (Linnaeus, 1758) Report on ITIS

Vernacular names

English: Northern Fur Seal

日本語: キタオットセイ

Polski: Kotik zwyczajny

Português: Foca-do-Alaska

-------

The Northern fur seal (Callorhinus ursinus) is an eared seal found along the north Pacific Ocean, the Bering Sea and the Sea of Okhotsk. It is the largest member of the fur seal subfamily (Arctocephalinae) and the only species in the genus Callorhinus.

Physical description

Male and harem

Northern fur seals have extreme sexual dimorphism, with males being 30–40% longer and more than 4.5 times heavier than adult females. The head is foreshortened in both sexes because of the very short down-curved muzzle, and small nose, which extends slightly beyond the mouth in females and moderately in males. The pelage is thick and luxuriant, with a dense underfur that is a creamy color. The underfur is obscured by the longer guard hairs, although it is partially-visible when the animals are wet. Features of both fore and hind flippers are unique and diagnostic of the species. Fur is absent on the top of the fored flippers and there is an abrupt "clean shaven line" across the wrist where the fur ends. The hind flippers are proportionately the longest in any otariid because of extremely long, cartilaginous extensions on all of the toes. There are small claws on digits 2–4, well back from the flap-like end of each digit. The ear pinnae are long and conspicuous, and naked of dark fur at the tips in older animals. The mystacial vibrissae can be very long, and regularly extend beyond the ears. Adults have all white vibrissae, juveniles and subadults have a mixture of white and black vibrissae, including some that have dark bases and white ends, and pups and yearlings have all-black vibrissae. The eyes are proportionately large and conspicuous, especially on females, subadults, and juveniles.

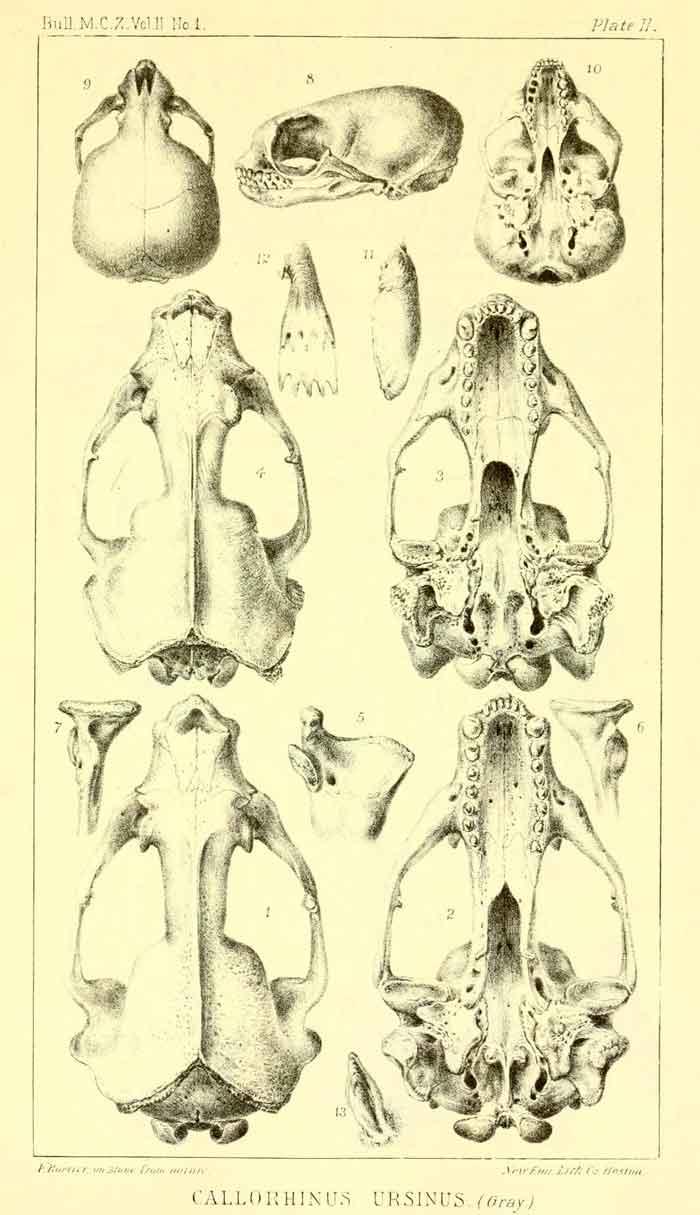

Adult males are stocky in build, and have an enlarged neck that is thick and wide. A mane of coarse longer guard hairs extends from the top of the head to the shoulders and covers the nape, neck, chest, and upper back. While the skull of adult males is large and robust for their overall size, the head appears short because of the combination of a short muzzle, and the back of the head behind the ear pinnae being obscured by the enlarged neck. Adult males have an abrupt forehead formed by the elevation of the crown from development of the sagittal crest, and thicker fur of the mane on the top of the head.

Canine teeth are much longer and have a greater diameter in adult males than those found on adult females, and this relationship holds to a lesser extent at all ages.

Fur seal pups, including one rare albino.

Adult females, subadults and juveniles, are moderate in build. It is difficult to distinguish the sexes until about age 5. The body is modest in size and the neck, chest, and shoulders are sized in proportion with the torso. Adult females and subadults have more complex and variable coloration than adult males. They are dark-silver-gray to charcoal above. The flanks, chest, sides, and underside of the neck, often forming a chevron pattern in this area, are cream to tan with rusty tones. There are variable cream to rust-colored areas on the sides and top of the muzzle, chin, and as a "brush stroke" running backwards under the eye. In contrast, adult males are medium gray to black, or reddish to dark brown all over. The mane can have variable amounts of silver-gray or yellowish tinting on the guard hairs. Pups are blackish at birth, with variable oval areas of buff on the sides, in the axillary area, and on the chin and sides of the muzzle. After 3–4 months, pups molt to the color of adult females and subadults.

Males can be as large as 2.1 m and 270 kg. Females can be up to 1.5 m and 50 kg or more. Newborns weigh 5.4–6 kg, and are 60–65 cm long.

The teeth are haplodont, i.e. sharp, conical and mostly single-rooted, as is common with carnivorous marine mammals adapted to tearing fish flesh. As with most Caniforms, the upper canines are prominent. The dental formula of the adult is:[2]

Dentition

3.1.4.2

2.1.4.1

Range

Overview of rookery

The northern fur seal is found in the north Pacific – its southernmost reach is a line that runs roughly from the southern tip of Japan to the southern tip of the Baja California peninsula, the Sea of Okhotsk and the Bering Sea. There are estimated to be around 1.1 million Northern Fur Seals across the range, of which roughly one half breeds on the Pribilof Islands in the east Bering Sea. Another 200–250,000 breed on the Commander Islands in the west Bering Sea and some 100,000 breed on Tyuleni Island off the coast of Sakhalin in the southwest Sea of Okhotsk and another 60–70,000 in the central Kuril Islands in Russia. Smaller rookeries (around 5,000 animals) are found on Bogoslof Island in the Aleutian Chain and San Miguel Island in the Channel Island group off the coast of California.[3] Recent evidence from stable isotope analysis of Holocene fur seal bone collagen (δ13C and δ15N) indicate that prior to the maritime fur trade, it was more common for these animals to breed at local rookeries in British Columbia, California and likely along much of the northwest coast of North America.[4]

During the winter months, northern fur seals display a net movement southward, with animals from Russian rookeries regularly entering Japanese and Korean waters in the Sea of Japan and Alaskan animals moving along the central and eastern Pacific as far as Baja California.

The northern fur seal's range overlaps almost exactly with that of Steller sea lions, with which they occasionally cohabit reproductive rookeries, notably in the Kurils, the Commander Islands and Tyuleni Island. The only other fur seal found in the northern hemisphere is the Guadalupe Fur Seal which overlaps slightly with the northern fur seal's range in California.

Ecology

Fur seals are opportunistic feeders, primarily feeding on pelagic fish and squid depending on local availability. Identified fish prey include hake, anchovy, herring, sand lance, capelin, pollock, mackerel and smelt. Their feeding behavior is primarily solitary.

Northern fur seals are preyed upon primarily by sharks and orcas. Occasionally, very young animals will be eaten by Steller sea lions. Occasional predation on live pups by arctic foxes has also been observed.

Due to very high densities of pups on reproductive rookeries and the early age at which mothers begin their foraging trips, mortality can be relatively high. Consequently, pup carcasses are important in enriching the diet of many scavengers, in particular gulls and arctic foxes.

Reproductive behavior

Seals aggregate on traditional breeding grounds (rookeries) in May. Generally older males (10 years and older) return first and compete for prime breeding spots on the rookeries. They will remain on the rookery fasting throughout the duration of the breeding season. The females come somewhat later and give birth shortly thereafter. Like all other otariids, northern fur seals are polygynous, with some males breeding with up to 50 females in a single breeding season. Unlike Steller sea lions, with whom they share habitat and some breeding sites, Northern fur seals are possessive of individual females in their harem, often aggressively competing with neighboring males for females. Deaths of females as a consequence of 'tug-of-war's have been recorded, though the males themselves are rarely seriously injured. Young males unable to acquire and maintain a territory of a harem typically aggregate in neighboring "haulouts" occasionally making incursions into the reproductive sections of the rookery in an attempt to displace an older male.

After remaining with their pups for the first eight to ten days of their life, females begin foraging trips lasting up to a week. These trips last for about four months before weaning, which happens abruptly, typically in October. Most of the animals on a rookery enter the water and disperse towards the end of November, typically migrating southward. Breeding site fidelity is generally high for fur seals females, though young males might disperse to other existing rookeries, or occasionally found new haulouts.

Peak mating occurs somewhat later than peak birthing from late June to late July. As with many other otariids, the fertilized egg undergoes delayed implantation: after the blastocyst stage occurs, development halts and implantantion occurs four months after fertilization. In total, gestation lasts for approximately one year, such that the pups born in a given summer are the product of the previous year's breeding cycle.

Status

Recently there has been increased concern about the status of fur seal populations, particularly in the Pribilof Islands, where there has been a roughly 50% decrease in pup-production since the 1970s and a continuing drop in pup production of about 6–7% per year. This has caused them to be listed as "vulnerable" under the U.S. Endangered Species Act and has led to an intensified research program into their behavioral and foraging ecology. Possible causes are increased predation by orcas, competition with fisheries and climate change effects, but there is, to date, no scientific consensus. The IUCN (2008) lists the species as globally threatened under the category "vulnerable".

Fur trade

Northern fur seals have been a staple food of native northeast Asian and Alaskan Inuit peoples for thousands of years. The arrival of Europeans to Kamchatka and Alaska in the 17th and 18th centuries, first from Russia and later from North America, was followed by a highly extractive commercial fur trade. The commercial fur trade was accelerated in 1786, when Gavriil Pribylov discovered St. George Island, a key rookery of the seals. An estimated 2.5 million seals were killed from 1786 to 1867. This trade led to a decline in fur seal numbers. Restrictions were first placed on fur seal harvest on the Pribilof Islands by the Russians in 1834. Shortly after the United States purchased Alaska from Russia in 1867, the U.S. Treasury was authorized to lease sealing privileges on the Pribilofs, which were granted somewhat liberally to the Alaska Commercial Company. From 1870 to 1909, pelagic sealing proceeded to take a significant toll on the fur seal population, such that the Pribilof population, historically numbering on the order of millions of individuals, reached a low of 216,000 animals in 1912.

Significant harvest was more or less arrested with the signing of the North Pacific Fur Seal Convention of 1911 by Great Britain (on behalf of Canada), Japan, Russia and the United States. The Convention of 1911 remained in force until the onset of hostilities among the signatories during World War II, and is also notable as the first international treaty to address the conservation of wildlife.[5] A successive convention was signed in 1957 and amended by a protocol in 1963. "The international convention was put into effect domestically by The Fur Seal Act of 1966 (Public Law 89-702)," said an Interior Department review of the history.[6] Currently, there is a subsistence hunt by the residents of St. Paul Island and an insignificant harvest in Russia.

References

1. ^ Gelatt, T. & Lowry, L. (2008). Callorhinus ursinus. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on 30 January 2009. Listed as Vulnerable (VU A2b)

2. ^ Chiasson, B. (August 1957). "The Dentition of the Alaskan Fur Seal". Journal of Mammalogy (Journal of Mammalogy, Vol. 38, No. 3) 38 (3): pp. 310–319. doi:10.2307/1376230. http://jstor.org/stable/1376230

3. ^ Ream, R.; Burkanov, V. (2005). "PICES XIV Annual Meeting" (PDF). Vladivostock, Russia. http://www.pices.int/publications/presentations/PICES_14/S3/Ream.pdf

4. ^ Szpak, Paul; "Orchard, Trevor J., Grocke, Darren R." (2009). "A Late Holocene vertebrate food web from southern Haida Gwaii (Queen Charlotte Islands, British Columbia)". Journal of Archaeological Science 36 (12): 2734–2741. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2009.08.013. http://uwo.academia.edu/PaulSzpak/Papers/156301/A-Late-Holocene-vertebrate-food-web-from-southern-Haida-Gwaii--Queen-Charlotte-Islands--British-Columbia-.

5. ^ "North Pacific Fur Seal Treaty of 1911". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. http://celebrating200years.noaa.gov/events/fursealtreaty/welcome.html#treaty.

6. ^ Baker, R.C., F. Wilke, C.H. Baltzo, 1970. The northern fur seal, U.S. Dep. Int., Fish Wildlf Serv., Circ. 336, overall quote pp. 2-4, 14-17. Quoted on 4th p. of PDF, in "Fisheries Management: An Historical Overview" by Clinton E. Atkinson; p. 114 of Marine Fisheries Review 50(4) 1988.

* R. Gentry: Behavior and Ecology of the Northern Fur Seal. Princeton University Press, 1998 ISBN 0-691-03345-5

* R. Nowak: Walker's Marine Mammals of The World. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999 ISBN 0-8018-7343-6

* J. E. King: Seals of the world. Cornell University Press, 1983 ISBN 0-8014-1568-3

* Randall R. Reeves, Brent S. Stewart, Phillip J. Clapham and James A. Powell (2002). National Audubon Society Guide to Marine Mammals of the World. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. ISBN 0375411410.

Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/"

All text is available under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License