Superregnum: Eukaryota

Cladus: Unikonta

Cladus: Opisthokonta

Cladus: Holozoa

Regnum: Animalia

Subregnum: Eumetazoa

Cladus: Bilateria

Cladus: Nephrozoa

Cladus: Protostomia

Cladus: Ecdysozoa

Cladus: Panarthropoda

Phylum: Arthropoda

Subphylum: Hexapoda

Classis: Insecta

Cladus: Dicondylia

Subclassis: Pterygota

Cladus: Metapterygota

Infraclassis: Neoptera

Cladus: Eumetabola

Cladus: Endopterygota

Superordo: Panorpida

Cladus: Antliophora

Ordo: Diptera

Subordo: Brachycera

Infraordo: Muscomorpha

Sectio: Schizophora

Subsectio: Acalyptrata

Superfamilia: Tephritoidea

Familia:Platystomatidae

Genera (123): Acanthoneuropsis – Achias – Aetha – Agadasys – Aglaioptera – Agrochira – Amphicnephes – Angelopteromyia – Angitula – Antineura – Apactoneura – Apiola – Asyntona – Atopocnema – Atopognathus – Bama – Boisduvalia – Brea – Bromophila – Chaetorivellia – Chaetostichia – Cladoderris – Cleitamia – Cleitamoides – Clitodoca – Coelocephala – Conicipithea – Conopariella – Dayomyia – Duomyia – Elassogaster – Engistoneura – Eosamphicnephes – Eudasys – Eumeka – Euprosopia – Eurypalpus – Euthyplatystoma – Euxestomoea – Federleyella – Furcamyia – Guamomyia – Himeroessa – Hysma – Icteracantha – Imugana – Inium – Laglaizia – Lambia – Lamprogaster – Lamprophthalma – Lenophila – Lophoplatystoma – Loxoceromyia – Loxoneura – Loxoneuroides – Lule – Lulodes – Mesoctenia – Metoposparga – Mezona – Microepicausta – Microlule – Micronesomyia – Mindanaia – Montrouziera – Naupoda – Neoardelio – Neoepidesma – Neohemigaster – Oeciotypa – Oedemachilus – Palpomya – Par – Parardelio – Paryphodes – Peltacanthina – Phasiamyia – Philocompus – Phlebophis – Phlyax – Phytalmodes – Piara – Picrometopus – Plagiostenopterina – Plastotephritis – Platystoma – Poecilotraphera – Pogonortalis – Polystodes – Prionoscelia – Prosopoconus – Prosthiochaeta – Pseudepicausta – Pseudocleitamia – Pseudorichardia – Pterogenia – Pterogenomyia – Rhegmatosaga – Rhytidortalis – Rivellia – Scelostenopterina – Scholastes – Scotinosoma – Seguyopiara – Signa – Sors – Sphenoprosopa – Stellapteryx – Stenopterina – Steyskaliella – Tarfa – Tomeus – Traphera – Trigonosoma – Valonia – Venacalva – Xenaspis – Xenaspoides – Xiria – Xyrogena – Zealandortalis – Zygaenula

Name

Platystomatidae Schiner, 1862

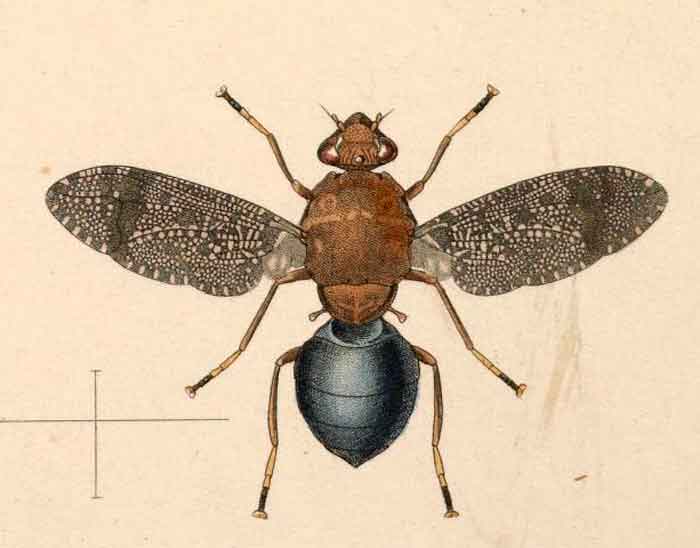

Peltacanthina pectoralis

References

Bodner, L. & Freidberg, A. 2016. Taxonomy and immature stages of the Platystomatidae (Diptera: Tephritoidea) of Israel. Zootaxa 4171(2): 201–245. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.4171.2.1 Reference page.

McAlpine, D.K., 2001: Review of the Australasian genera of signal flies (Diptera: Platystomatidae). Records of the Australian Museum, 53 (2): 113–199. ISSN: 0067-1975 DOI: 10.3853/j.0067-1975.53.2001.1327

McAlpine, D.K., 2011: Queensland signal flies of the Duomyia ameniina alliance (Diptera: Platystomatidae) and a related new species. Tijdschrift voor Entomologie 154 (1): 61–73.

Roy, S., Parui, P. & Mitra, B. 2017. Plagiostenopterina sagarensis sp. nov. (Diptera: Platystomatidae: Platystomatinae) from Sunderban Biosphere Reserve, India with a key to Indian species. Zootaxa 4294(4): 487–493. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.4294.4.8. Reference page.

Roy, S., Parui, P. & Mitra, B. 2017. CORRIGENDA. SANKARSAN ROY, PANCHANAN PARUI & BULGANIN MITRA (2017) Plagiostenopterina sagarensis sp. nov. (Diptera: Platystomatidae: Platystomatinae) from Sunderban Biosphere Reserve, India with a key to Indian species. Zootaxa, 4294: 487–493. Zootaxa 4318(3): 600–600. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.4318.3.12. Reference page.

Wendt, L.D. 2016. FAMILY PLATYSTOMATIDAE. In Wolff, M.I., Nihei, S.S. & Carvalho, C.J.B. de (eds.), Catalogue of Diptera of Colombia. Zootaxa 4122(1): 579–581. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.4122.1.47. Reference page.

Links

CU*STAR Version 6.0 [1]

The Platystomatidae (signal flies) are a distinctive family of flies (Diptera) in the superfamily Tephritoidea.

Signal flies are worldwide in distribution, found in all the biogeographic realms, but predominate in the tropics. It is one of the larger families of acalyptrate Diptera with around 1200 species in 127 genera.

Biology

Adults are found on tree trunks and foliage and are attracted to flowers, decaying fruit, excrement, sweat, and decomposing snails.[2][3] Larvae are found on fresh and decaying vegetation, carrion, human corpses, and root nodules, particularly in the genus Rivellia, which has economic implications for legume crops.[4] Larvae from the remaining genera are either phytophagous (eating plant material) or saprophagous (eating decomposing organic matter). Some are predatory on other insects and others have been found in human lesions, while others are of minor agricultural significance.

Family description

For terms see Morphology of Diptera

Signal flies are very variable in external appearance, ranging from small (2.5 mm), slender species to large (20 mm), robust individuals, often with body colours having a distinctive metallic lustre and with face and wings usually patterned with dark spots or bands. The head is large. Frontal bristles on head are absent. Two orbital bristles are on the head. The frontal stripe is pubescent and the arista is more or less long and pubescent. The antennal grooves are deep and divided by a median keel. Radial vein 4+5 bears bristles. The costa is without interruptions and the anal cell is elongated, bordered on outer side by an arcuate or straight vein. The abdomen of male has five visible segments and the female has six.

Pogonortalis doclea

Peltacanthina species

Many bizarre forms of morphology and behaviour occur in this family. Heads and legs (fore legs especially) may be oddly shaped, extended in various ways or with adornments, all of which serve to supplement agonistic behaviour. Such behaviour underlies social and sexual interaction between individuals of the same species of signal flies, first researched in Australian species of the genera Euprosopia image and Pogonortalis[5]

In males of Pogonortalis, the length and degree of development of hairs (setae) on the lower facial area, together with widening of the head, facilitates territorial dominance[6] by head-butting and rearing-up behaviours. Head-butting is taken to the extreme in the Australasian genus Achias,[7][8] in which species have the fronto-orbital plates expanded laterally to produce eyestalks.

Development of body structures is prevalent in the Afrotropical and Oriental subfamily Plastotephritinae,[9] including 9 different types of modification in 16 genera.[10]

Plate from Novitates Zoologicae showing the great variation in eyestalk development in Achias rothschildi

Plate from Revue et Magasin de Zoologie depicting Pterogenia singularis Bigot, 1859

Some species have prominent eyestalks also found in the family Diopsidae. In the Diopsidae, eyestalks develop through lateral development of the frontal plate, with the result that the antennae are situated on the stalk near the compound eye. The process of development in signal flies is different in that the fronto-orbital plates expanded laterally to produce eyestalks and consequently the antennae remain in a central position. This is an example of convergent evolution. The development of eyestalks reaches its extreme in the platystomatid species Achias rothschildi Austen, 1910 from New Guinea, pictured here in which males have an eye-span up to 55 mm.[11]

Families of acalyptrate flies exhibiting morphological development associated with agonistic behaviour include: Clusiidae, Diopsidae, Drosophilidae, Platystomatidae, Tephritidae, and Ulidiidae.

See also [1]

Biogeography

The largest concentration of Platystomatidae undoubtedly occurs in the Australasian region,[12] followed closely by the Afrotropical region. The number of genera and species in the Oriental, European,[13] Nearctic and Neotropical faunas are much more restricted and are summarised in the Regional Catalogues.

Some genera are widely distributed over more than one region. For example, Plagiostenopterina Hendel, 1912,[14] is widely distributed in the Old World tropics (Australasian, Oriental and Afrotropical regions) and Rivellia Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830[15] is almost cosmopolitan,[12] although numbers of species in Europe are very restricted in number. Taxonomic revisions of such genera need to examine the wider implications of these broad distributions. Other genera are known from just a single location. Bama McAlpine, 2001, for example, is known only from New Guinea.[12]

Taxonomic history

As is the case with the taxonomy many flies, the first described species of Platystomatidae were placed in the large family Muscidae, because in the 19th century, the Muscidae formed a portmanteau group for the higher Diptera. It was only after many species were accumulated into larger collections and numerous names proposed, that taxonomists began to realise that the Diptera consisted of several distinct families.

The oldest family-group name for the Platystomatidae is in fact Achiasidae Fleming, 1821,[16] based on the genus Achias Fabricius, 1805.[17] There has, however, been an overwhelming predominance of the usage of names based on the genus Platystoma Meigen, 1803.[18] After petition by Steyskal & McAlpine (1974),[19] the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (1979) ruled under plenary power that family-group names based on Achias should be suppressed, giving those based on Platystoma precedence.[20]

Initially, subfamilies within the Muscidae were recognised; the early Platystomatidae belonging to the Ortalides, but toward the end of the 19th century, many of these subfamilies were raised to family status, at which point the Ortalides became the Ortalidae. The name Otitidae became a replacement name for Ortalides, until Hendel's significant contribution and re-organisation of the genera of the World [21] firmly placed the Platystomatidae as a subfamily of Muscaridae, divided into several tribes. Furthermore, he recognised the broad divisions Acalyptrae and Calyptrae, placing Platystomatinae correctly in the former. Enderlein, who proposed more new plastotephritine (subfamily) names than Hendel, still preferred Ortalidae to Muscaridae, but adopted the Platystomatinae subfamily status that Hendel had proposed.[22][23]

See also

List of Platystomatidae genera

References

Biolib

McAlpine, D K (1973) The Australian Platystomatidae (Diptera, Schizophora) with a revision of five genera. The Australian Museum Memoirs 15: 1–256.

Ferrar, P (1987) A guide to the breeding habits and immature stages of Diptera Cyclorrhapha (Part 1: text; Part 2: figures). Entomonograph 8: 1–478.

Whittington, A E (2019) The economic significance of the signal fly genus Rivellia Robineau-Desvoidy (Diptera: Platystomatidae). Israel Journal of Entomology 49(2): 135–160.

McAlpine, D K (1973) Observations on sexual behaviour in some Australian Platystomatidae (Diptera, Schizophora). Records of the Australian Museum 29(1): 1–10.

McAlpine, D K (1975) Combat between males of Pogonortalis doclea (Diptera, Platystomatidae) and its relation to structural modification. Australian Entomological Magazine 2(5): 104–107.

McAlpine, D K (1979) Agonistic behavior in Achias australis (Diptera, Platystomatidae) and the significance of eyestalks. In: Blum, M S and Blum, N A (eds). Sexual selection and reproductive competition in insects. Academic Press, New York.

McAlpine, D K (1994) Review of the species of Achias (Diptera: Platystomatidae). Invert. Taxon. 8(1): 117–281.

Whittington, A E (2003) Taxonomic revision of the Afrotropical Plastotephritinae (Diptera; Platystomatidae). Studia dipterologica Supplement 12: 1–300.

Whittington, A E (2006) Extreme head morphology in Plastotephritinae (Diptera, Platystomatidae), with a proposition of classification of head structures in Acalyptrate Diptera. Instrumenta Biodiversitatis VII: 61–83.

Arnauld, P H Jr (1994) Frontispieces: Achias rothschildi Austen (Diptera: Platystomatidae). Myia 5: iv.

McAlpine, D K (2001). "Review of the Australian Genera of Signal Flies (Diptera; Platystomatidae)". Records of the Australian Museum. 53 (2): 113–119. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.53.2001.1327.

Korneyev V A (2001) A Key to Genera of Palaearctic Platystomatidae (Diptera), with descriptions of a new genus and new species. Entomological Problems (Bratislava), 32(1): 1–16.

Hendel, F (1912) Neue muscidae acalyptratae. Wiener Entomologischen Zeitung 31: 1–20.

Robineau-Desvoidy, J.B. (1830). "Essai sur les myodaires". Mémoires présentés par divers savans à l'Académie Royale des Sciences de l'Institut de France (Sciences Mathématiques et Physiques). 2 (2): 1–813. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

Fleming, J (1821) Insects. In: Stewart, D & Napier, M (eds.). Supplement to the 4th, 5th and 6th editions of the Encyclopaedia Britannica 5(1): 846. Edinburgh: A Constable & Co.

Fabricius, Johann Christian (1805). Systema antliatorum secundum ordines, genera, species. Bransvigae: Apud Carolum Reichard. pp. i–xiv, 1–373. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

Meigen, J-B (1803). "Versuch einer neuen Gattungs Einteilung der eropäischen zweiflügligen Insekten". Magazin für Insektenkunde (Illiger). 2: 259–281.

Steyskal, G C and McAlpine, D K (1974) Platystomatidae Schiner, 1862: Proposed conservation as a family-group name over Achiidae Fleming, 1821 (Insecta, Diptera). Z.N.(S.) 2053. Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature 31(1): 59–61.

International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (1979) Opinion 1142. Family-group names based on Platystoma Meigen, 1803, given precedence over those based on Achias Fabricius, 1805 (Diptera). Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature 36(2): 125–129.

Hendel, F (1914a) Diptera Fam. Muscaridae Subfam. Platystominae. Genera Insectorum 157: 1–179.

Enderlein, G (1922) Die Platystominentribus Plastotephritini. Stettiner Entomologische Zeitung 83: 3–16.

Enderlein, Günther (1924). "Beitrage zur Kenntnis der Platystominen". Mitteilungen aus dem Zoologischen: 99–153.

Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/"

All text is available under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License