.

Braid group

In mathematics, the braid group on n strands, denoted by Bn, is a group which has an intuitive geometrical representation, and in a sense generalizes the symmetric group Sn. Here, n is a natural number; if n > 1, then Bn is an infinite group. Braid groups find applications in knot theory, since any knot may be represented as the closure of certain braids.

Introduction

Intuitive description

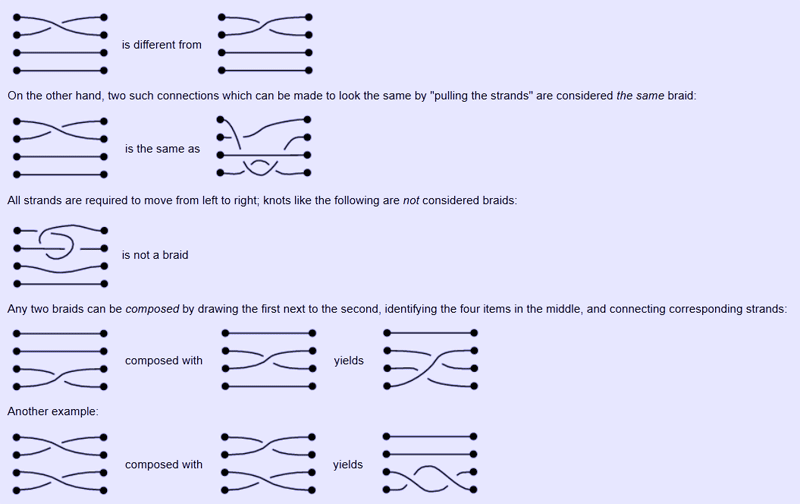

This introduction takes n to be 4; the generalization to other values of n will be straightforward. Consider two sets of four items lying on a table, with the items in each set being arranged in a vertical line, and such that one set sits next to the other. (In the illustrations below, these are the black dots.) Using four strands, each item of the first set is connected with an item of the second set so that a one-to-one correspondence results. Such a connection is called a braid. Often some strands will have to pass over or under others, and this is crucial: the following two connections are different braids:

The composition of the braids σ and τ is written as στ.

The set of all braids on four strands is denoted by B4. The above composition of braids is indeed a group operation. The neutral element is the braid consisting of four parallel horizontal strands, and the inverse of a braid consists of that braid which "undoes" whatever the first braid did. (The first two example braids above are inverses of each other.)

Formal treatment

To put the above informal discussion of braid groups on firm ground, one needs to use the homotopy concept of algebraic topology, defining braid groups as fundamental groups of a configuration space. This is outlined in the article on braid theory.

Alternatively, one can eschew topology altogether and define the braid group purely algebraically via the braid relations, keeping the pictures in mind only to guide the intuition.

History

Braid groups were introduced explicitly by Emil Artin in 1925, although (as Wilhelm Magnus pointed out in 1974[1]) they were already implicit in Adolf Hurwitz's work on monodromy (1891). In fact, as Magnus says, Hurwitz gave the interpretation of a braid group as the fundamental group of a configuration space (cf. braid theory), an interpretation that was lost from view until it was rediscovered by Ralph Fox and Lee Neuwirth in 1962.

Basic properties

Generators and relations

Consider the following three braids:

Every braid in B4 can be written as a composition of a number of these braids and their inverses. In other words, these three braids generate the group B4. To see this, an arbitrary braid is scanned from left to right; whenever a crossing of strands i and i + 1 (counting from the top at the point of the crossing) is encountered, σi or σi−1 is written down, depending on whether strand i moves under or over strand i + 1. Upon reaching the right hand end, the braid has been written as a product of the σ's and their inverses.

It is clear that (i):σ1σ3 = σ3σ1, while the following two relations are not quite as obvious: (iia):σ1σ2σ1 = σ2σ1σ2, (iib):σ2σ3σ2 = σ3σ2σ3 (these can be appreciated best by drawing the braid on a piece of paper). It can be shown that all other relations among the braids σ1, σ2 and σ3 already follow from these relations and the group axioms.

Generalising this example to n strands, the group Bn can be abstractly defined via the following presentation:

\( B_n=\langle \sigma_1,\ldots,\sigma_{n-1}| \sigma_i\sigma_{i+1}\sigma_i=\sigma_{i+1}\sigma_i\sigma_{i+1}, \sigma_i\sigma_j=\sigma_j\sigma_i \rangle, \)

where in the first group of relations 1 ≤ i ≤ n−2 and in the second group of relations, |i − j| ≥ 2. This presentation leads to generalisations of braid groups called Artin groups. The cubic relations, known as the braid relations, play an important role in the theory of Yang–Baxter equation.

Further properties

- The braid group B1 is trivial, B2 is an infinite cyclic group Z, and B3 is isomorphic to the knot group of the trefoil knot – in particular, it is an infinite non-abelian group.

- The n-strand braid group Bn embeds as a subgroup into the (n+1)-strand braid group Bn+1 by adding an extra strand that does not cross any of the first n strands. The increasing union of the braid groups with all n ≥ 1 is the infinite braid group B∞.

- All non-identity elements of Bn have infinite order: Bn is torsion-free.

- Patrick Dehornoy constructed a left-invariant linear order on Bn called the Dehornoy order.

- For n ≥ 3, Bn contains a subgroup isomorphic to the free group on two generators.

- There is a homomorphism Bn → Z that maps every σi to 1. So for instance, the braid σ2σ3σ1−1σ2σ3 is mapped to 1 + 1 − 1 + 1 + 1 = 3.

Interactions of braid groups

Relation with symmetric group and the pure braid group

By forgetting how the strands twist and cross, every braid on n strands determines a permutation on n elements. This assignment is onto, compatible with composition, and therefore becomes a surjective group homomorphism Bn → Sn from the braid group into the symmetric group. The image of the braid σi ∈ Bn is the transposition si = (i, i+1) ∈ Sn. These transpositions generate the symmetric group, satisfy the braid group relations, and have order 2. This transforms the Artin presentation of the braid group into the Coxeter presentation of the symmetric group:

\( S_n=\langle s_1,\ldots,s_{n-1}| s_i s_{i+1} s_i=s_{i+1} s_i s_{i+1}, s_i s_j = s_j s_i ~\rm{for}~|i-j|\geq 2, s_i^2=1 \rangle. \)

The kernel of the homomorphism Bn → Sn is the subgroup of Bn called the pure braid group on n strands and denoted Pn. In a pure braid, the beginning and the end of each strand are in the like positions. Pure braid groups fit into a short exact sequence

\( 1\to F_{n-1} \to P_n \to P_{n-1}\to 1.\)

This sequence splits and therefore pure braid groups are realized as iterated semi-direct products of free groups.

Relation between B3 and the modular group

B3 is the universal central extension of the modular group.

The braid group B3 is the universal central extension of the modular group PSL(2,Z), with these sitting as lattices inside the (topological) universal covering group \( \overline{\mathrm{SL}(2,\mathbf{R})} \to \mathrm{PSL}(2,\mathbf{R}). \)

Further, the modular group has trivial center, and thus the modular group is isomorphic to the quotient group of \( B_3 \) modulo its center; equivalently, to the group of inner automorphisms of \( B_3 \).

A construction is given below.

Define \( a = \sigma_1 \sigma_2 \sigma_1 \) and \( b = \sigma_1 \sigma_2 \). From the braid relations it follows that \( a^2=b^3 \). Denoting this latter product as \( c=a^2=b^3 \), one may verify from the braid relations that

\( \sigma_1 c \sigma_1^{-1} = \sigma_2 c \sigma_2^{-1}=c \)

implying that c is in the center of B3. The subgroup \( \langle c\rangle \) of B3 generated by c is therefore a normal subgroup. Since it is normal, one may take the quotient group; this quotient group is isomorphic to the modular group:

\( PSL(2,\mathbf{Z}) \simeq B_3/\langle c\rangle. \)

This isomorphism can be given an explicit form. The cosets \( [\sigma_1] \) of \( \sigma_1 \) and \([\sigma_2] \) of \( \sigma_2 \) map to

\( [\sigma_1] \mapsto R=\begin{bmatrix}1 & 1 \\ 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \qquad [\sigma_2] \mapsto L^{-1}=\begin{bmatrix}1 & 0 \\ -1 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \)

where L and R are the standard left and right moves on the Stern-Brocot tree; it is well known that these moves generate the modular group.

Alternately, one common presentation for the modular group is

\( \langle v,p\, |\, v^2=p^3=1\rangle \)

where

\( v=\begin{bmatrix}0 & 1 \\ -1 & 0 \end{bmatrix}, \qquad p=\begin{bmatrix}0 & 1 \\ -1 & 1 \end{bmatrix}. \)

Mapping a to v and b to p yields a surjective group homomorphism from B3 to PSL(2,Z).

The center of B3 is equal to \( \langle c\rangle \), a consequence of the facts that c is in the center, the modular group has trivial center, and the above surjective homomorphism has kernel \( \langle c\rangle.

\)

Relationship to the mapping class group and classification of braids

The braid group Bn can be shown to be isomorphic to the mapping class group of a punctured disk with n punctures. This is most easily visualized by imagining each puncture as being connected by a string to the boundary of the disk; each mapping homeomorphism that permutes two of the punctures can then be seen to be a homotopy of the strings, that is, a braiding of these strings.

Via this mapping class group interpretation of braids, each braid may be classified as periodic, reducible or pseudo-Anosov.

Connection to knot theory and computational aspects

If a braid is given and one connects the first left-hand item to the first right-hand item using a new string, the second left-hand item to the second right-hand item etc. (without creating any braids in the new strings), one obtains a link, and sometimes a knot. Alexander's theorem in braid theory states that the converse is true as well: every knot and every link arises in this fashion from at least one braid; such a braid can be obtained by cutting the link. Since braids can be concretely given as words in the generators σi, this is often the preferred method of entering knots into computer programs.

The word problem for the braid relations is efficiently solvable and there exists a normal form for elements of Bn in terms of the generators σ1,...,σn−1. (In essence, computing the normal form of a braid is the algebraic analogue of "pulling the strands" as illustrated in our second set of images above.) The free GAP computer algebra system can carry out computations in Bn if the elements are given in terms of these generators. There is also a package called CHEVIE for GAP3 with special support for braid groups. The word problem is also efficiently solved via the Lawrence-Krammer representation.

Since there are nevertheless several hard computational problems about braid groups, applications in cryptography have been suggested.

Actions of braid groups

In analogy with the action of the symmetric group by permutations, in various mathematical settings there exists a natural action the braid group on n-tuples of objects or on the n-folded tensor product that involves some "twists". Consider an arbitrary group G and let X be the set of all n-tuples of elements of G whose product is the identity element of G. Then Bn acts on X in the following fashion:

\( \sigma_i(x_1,\ldots,x_{i-1},x_i, x_{i+1},\ldots, x_n)= (x_1,\ldots, x_{i-1}, x_{i+1}, x_{i+1}^{-1}x_i x_{i+1}, x_{i+2},\ldots,x_n). \)

Thus the elements xi and xi+1 exchange places and, in addition, xi is twisted by the inner automorphism corresponding to xi+1 — this ensures that the product of the components of x remains the identity element. It may be checked that the braid group relations are satisfied and this formula indeed defines a group action of Bn on X. As another example, a braided monoidal category is a monoidal category with a braid group action. Such structures play an important role in modern mathematical physics and lead to quantum knot invariants.

Representations

Elements of the braid group Bn can be represented more concretely by matrices. One classical such representation is Burau representation, where the matrix entries are single variable Laurent polynomials. It had been a long-standing question whether Burau representation was faithful, but the answer turned out to be negative for n ≥ 5. More generally, it was a major open problem whether braid groups were linear. In 1990, Ruth Lawrence described a family of more general "Lawrence representations" depending on several parameters. Around 2001 Stephen Bigelow and Daan Krammer independently proved that all braid groups are linear. Their work used the Lawrence–Krammer representation of dimension n(n−1)/2 depending on the variables q and t. By suitably specializing these variables, the braid group Bn may be realized as a subgroup of the general linear group over the complex numbers.

Infinitely generated braid groups

There are many ways to generalize this notion to an infinite number of strands. The simplest way is take the direct limit of braid groups, where the attaching maps \( f:B_n\to B_{n+1} \) send the n-1 generators of \( B_n \) to the first n-1 generators of \( B_{n+1} \) (i.e., by attaching a trivial strand). Fabel has shown that there are two topologies that can be imposed on the resulting group each of whose completion yields a different group. One is a very tame group and is isomorphic to the mapping class group of the infinitely punctured disk — a discrete set of punctures limiting to the boundary of the disk.

The second group can be thought of the same as with finite braid groups. Place a strand at each of the points (0,1/n) and the set of all braids — where a braid is defined to be a collection of paths from the points (0,1/n,0) to the points (0,1/n,1) so that the function yields a permutation on endpoints — is isomorphic to this wilder group. An interesting fact is that the pure braid group in this group is isomorphic to both the inverse limit of finite pure braid groups P_n and to the fundamental group of the Hilbert cube minus the set \( \{(x_i)_{i\in \Bbb{N}} \mid x_i=x_j\text{ for some }i\ne j\}. \)

Notes

^ Wilhelm Magnus. Braid groups: A survey. In Lecture Notes in Mathematics, volume 372, pages 463–487. Springer, 1974. Proceedings of the Second International Conference on the Theory of Groups, Canberra, Australia, 1973. ISBN 978-3-540-06845-7

References

Deligne, Pierre (1972), "Les immeubles des groupes de tresses généralisés", Inventiones Mathematicae 17 (4): 273–302, doi:10.1007/BF01406236, ISSN 0020-9910, MR 0422673

Further reading

Birman, Joan, and Brendle, Tara E., "Braids: A Survey", revised 26 February 2005. In Menasco and Thistlethwaite.

Carlucci, Lorenzo; Dehornoy, Patrick; and Weiermann, Andreas, "Unprovability results involving braids", 23 November 2007

Kassel, Christian; and Turaev, Vladimir, Braid Groups, Springer, 2008. ISBN 0-387-33841-1

Menasco, W., and Thistlethwaite, M., (editors), Handbook of Knot Theory, Amsterdam : Elsevier, 2005. ISBN 0-444-51452-X

External links

Braid group, PlanetMath.org.

CRAG: CRyptography and Groups at Algebraic Cryptography Center Contains extensive library for computations with Braid Groups

P. Fabel, Completing Artin's braid group on infinitely many strands, Journal of Knot Theory and its Ramifications, Vol. 14, No. 8 (2005) 979–991

P. Fabel, The mapping class group of a disk with infinitely many holes, Journal of Knot Theory and its Ramifications, Vol. 15, No. 1 (2006) 21–29

Chernavskii, A.V. (2001), "Braid theory", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104

Stephen Bigelow's exploration of B5 Java applet.

Cryptography and Braid Groups page - Helger Lipmaa

Braid group: (List of Authority Articles on arxiv.org:

Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/"

All text is available under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License