In mathematics, hyperbolic geometry is a non-Euclidean geometry, meaning that the parallel postulate of Euclidean geometry is replaced. The parallel postulate in Euclidean geometry states, for two dimensions, that given a line l and a point P not on l, there is exactly one line through P that does not intersect l; i.e., that is parallel to l. In hyperbolic geometry there are at least two distinct lines through P which do not intersect l, so the parallel postulate is false. Models have been constructed within Euclidean geometry that obey the axioms of hyperbolic geometry, thus proving that the parallel postulate is independent of the other postulates of Euclid.

Since there is no precise hyperbolic analogue to Euclidean parallel lines, the hyperbolic use of parallel and related terms varies among writers. In this article, the two limiting lines are called asymptotic and lines sharing a common perpendicular are called ultraparallel; the simple word parallel may apply to both.

Non-intersecting lines

An interesting property of hyperbolic geometry follows from the occurrence of more than one parallel line through a point P: there are two classes of non-intersecting lines. Let B be the point on l such that the line PB is perpendicular to l. Consider the line x through P such that x does not intersect l, and the angle θ between PB and x counterclockwise from PB is as small as possible; i.e., any smaller angle will force the line to intersect l. This is called an asymptotic line in hyperbolic geometry. Symmetrically, the line y that forms the same angle θ between PB and itself but clockwise from PB will also be asymptotic. x and y are the only two lines asymptotic to l through P. All other lines through P not intersecting l, with angles greater than θ with PB, are called ultraparallel (or disjointly parallel) to l. Notice that since there are an infinite number of possible angles between θ and 90 degrees, and each one will determine two lines through P and disjointly parallel to l, there exist an infinite number of ultraparallel lines.

Thus we have this modified form of the parallel postulate: In hyperbolic geometry, given any line l, and point P not on l, there are exactly two lines through P which are asymptotic to l, and infinitely many lines through P ultraparallel to l.

The differences between these types of lines can also be looked at in the following way: the distance between asymptotic lines shrinks toward zero in one direction and grows without bound in the other; the distance between ultraparallel lines (eventually) increases in both directions. The ultraparallel theorem states that there is a unique line in the hyperbolic plane that is perpendicular to each of a given pair of ultraparallel lines.

In Euclidean geometry, the angle of parallelism is a constant; that is, any distance ![]() between parallel lines yields an angle of parallelism equal to 90°. In hyperbolic geometry, the angle of parallelism varies with the Π(p) function. This function, described by Nikolai Ivanovich Lobachevsky, produces a unique angle of parallelism for each distance

between parallel lines yields an angle of parallelism equal to 90°. In hyperbolic geometry, the angle of parallelism varies with the Π(p) function. This function, described by Nikolai Ivanovich Lobachevsky, produces a unique angle of parallelism for each distance ![]() . As the distance gets shorter, Π(p) approaches 90°, whereas with increasing distance Π(p) approaches 0°. Notice that due to this fact, as distances get smaller, the hyperbolic plane behaves more and more like Euclidean geometry. On small scales, therefore, an observer would have a hard time determining whether he is in the Euclidean or the hyperbolic plane.

. As the distance gets shorter, Π(p) approaches 90°, whereas with increasing distance Π(p) approaches 0°. Notice that due to this fact, as distances get smaller, the hyperbolic plane behaves more and more like Euclidean geometry. On small scales, therefore, an observer would have a hard time determining whether he is in the Euclidean or the hyperbolic plane.

History

A number of geometers made attempts to prove the parallel postulate by assuming its negation and trying to derive a contradiction, including Proclus, Ibn al-Haytham (Alhacen), Omar Khayyám,[1] Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, Witelo, Gersonides, Alfonso, and later Giovanni Gerolamo Saccheri, John Wallis, Lambert, and Legendre.[1] Their attempts failed, but their efforts gave birth to hyperbolic geometry.

The theorems of Alhacen, Khayyam and al-Tusi on quadrilaterals, including the Lambert quadrilateral and Saccheri quadrilateral, were the first theorems on hyperbolic geometry. Their works on hyperbolic geometry had a considerable influence on its development among later European geometers, including Witelo, Gersonides, Alfonso, John Wallis and Saccheri.[2]

In the nineteenth century, hyperbolic geometry was extensively explored by János Bolyai and Nikolai Ivanovich Lobachevsky, after whom it sometimes is named. Lobachevsky published in 1830, while Bolyai independently discovered it and published in 1832. Karl Friedrich Gauss also studied hyperbolic geometry, describing in a 1824 letter to Taurinus that he had constructed it, but did not publish his work. In 1868, Eugenio Beltrami provided models of it, and used this to prove that hyperbolic geometry was consistent if Euclidean geometry was.

The term "hyperbolic geometry" was introduced by Felix Klein in 1871[3].

For more history, see article on non-Euclidean geometry, and the references Coxeter and Milnor.

Models of the hyperbolic plane

There are four models commonly used for hyperbolic geometry: the Klein model, the Poincaré disc model, the Poincaré half-plane model, and the Lorentz model, or hyperboloid model. These models define a real hyperbolic space which satisfies the axioms of a hyperbolic geometry. Despite the naming, the two disc models and the half-plane model were introduced as models of hyperbolic space by Beltrami, not by Poincaré or Klein.

1. The Klein model, also known as the projective disc model and Beltrami-Klein model, uses the interior of a circle for the hyperbolic plane, and chords of the circle as lines.

* This model has the advantage of simplicity, but the disadvantage that angles in the hyperbolic plane are distorted.

* The distance in this model is the cross-ratio, which was introduced by Arthur Cayley in projective geometry.

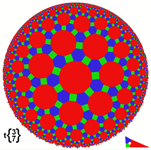

2. The Poincaré disc model, also known as the conformal disc model, also employs the interior of a circle, but lines are represented by arcs of circles that are orthogonal to the boundary circle, plus diameters of the boundary circle.

3. The Poincaré half-plane model takes one-half of the Euclidean plane, as determined by a Euclidean line B, to be the hyperbolic plane (B itself is not included).

* Hyperbolic lines are then either half-circles orthogonal to B or rays perpendicular to B.

* Both Poincaré models preserve hyperbolic angles, and are thereby conformal. All isometries within these models are therefore Möbius transformations.

4. The Lorentz model or hyperboloid model employs a 2-dimensional hyperboloid of revolution (of two sheets, but using one) embedded in 3-dimensional Minkowski space. This model is generally credited to Poincaré, but Reynolds (see below) says that Wilhelm Killing and Karl Weierstrass used this model from 1872.

* This model has direct application to special relativity, as Minkowski 3-space is a model for spacetime, suppressing one spatial dimension. One can take the hyperboloid to represent the events that various moving observers, radiating outward in a spatial plane from a single point, will reach in a fixed proper time. The hyperbolic distance between two points on the hyperboloid can then be identified with the relative rapidity between the two corresponding observers.

Visualizing hyperbolic geometry

M. C. Escher's famous prints Circle Limit III and Circle Limit IV illustrate the conformal disc model quite well. In both one can see the geodesics. (In III the white lines are not geodesics, but hypercycles, which run alongside them.) It is also possible to see quite plainly the negative curvature of the hyperbolic plane, through its effect on the sum of angles in triangles and squares.

For example, in Circle Limit III every vertex belongs to three triangles and three squares. In the Euclidean plane, their angles would sum to 450°; i.e., a circle and a quarter. From this we see that the sum of angles of a triangle in the hyperbolic plane must be smaller than 180°. Another visible property is exponential growth. In Circle Limit IV, for example, one can see that the number of demons within a distance of n from the center rises exponentially. The demons have equal hyperbolic area, so the area of a ball of radius n must rise exponentially in n.

There are several ways to physically realize a hyperbolic plane (or approximation thereof). A particularly well-known paper model based on the pseudosphere is due to William Thurston. The art of crochet has been used to demonstrate hyperbolic planes with the first being made by Daina Taimina.[4] In 2000, Keith Henderson demonstrated a quick-to-make paper model dubbed the "hyperbolic soccerball".

Relationship to Riemann surfaces

Two-dimensional hyperbolic surfaces can also be understood according to the language of Riemann surfaces. According to the uniformization theorem, every Riemann surface is either elliptic, parabolic or hyperbolic. Most hyperbolic surfaces have a non-trivial fundamental group π1 = Γ; the groups that arise this way are known as Fuchsian groups. The quotient space H/Γ of the upper half-plane modulo the fundamental group is known as the Fuchsian model of the hyperbolic surface. The Poincaré half plane is also hyperbolic, but is simply connected and noncompact. It is the universal cover of the other hyperbolic surfaces.

The analogous construction for three-dimensional hyperbolic surfaces is the Kleinian model.

Links

* Visions of Infinity: Tiling a hyperbolic floor inspires both mathematics and art Science News: Dec. 23, 2000; Vol. 158, No. 26/27, p. 408

* "The Hyperbolic Geometry Song" A short music video about the basics of Hyperbolic Geometry available at Youtube.

* Eric W. Weisstein, Gauss-Bolyai-Lobachevsky Space at MathWorld.

* More on hyperbolic geometry, including movies and equations for conversion between the different models University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

References

1. ^ See for instance, Omar Khayyam 1048-1131. Retrieved on 2008-01-05.

2. ^ Boris A. Rosenfeld and Adolf P. Youschkevitch (1996), "Geometry", in Roshdi Rashed, ed., Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science, Vol. 2, p. 447-494 [470], Routledge, London and New York:

"Three scientists, Ibn al-Haytham, Khayyam and al-Tusi, had made the most considerable contribution to this branch of geometry whose importance came to be completely recognized only in the ninteenth century. In essence their propositions concerning the properties of quadrangles which they considered assuming that some of the angles of these figures were acute of obtuse, embodied the first few theorems of the hyperbolic and the elliptic geometries. Their other proposals showed that various geometric statements were equivalent to the Euclidean postulate V. It is extremely important that these scholars established the mutual connection between tthis postulate and the sum of the angles of a triangle and a quadrangle. By their works on the theory of parallel lines Arab mathematicians directly influenced the relevant investiagtions of their European couterparts. The first European attempt to prove the postulate on parallel lines - made by Witelo, the Polish scientists of the thirteenth century, while revising Ibn al-Haytham's Book of Optics (Kitab al-Manazir) - was undoubtedly prompted by Arabic sources. The proofs put forward in the fourteenth century by the Jewish scholar Levi ben Gerson, who lived in southern France, and by the above-mentioned Alfonso from Spain directly border on Ibn al-Haytham's demonstration. Above, we have demonstrated that Pseudo-Tusi's Exposition of Euclid had stimulated borth J. Wallis's and G. Saccheri's studies of the theory of parallel lines."

3. ^ F. Klein, Über die sogenannte Nicht-Euklidische, Geometrie, Math. Ann. 4, 573-625 (cf. Ges. Math. Abh. 1, 244-350).

4. ^ Hyperbolic Space. The Institute for Figuring (December 21, 2006). Retrieved on January 15, 2007.

"Visualizing Hyperbolic Geometry", Evelyn Lamb

Hyperbolic Geometry 1 : Geometry from Symmetries

Literature

* Coxeter, H. S. M. (1942) Non-Euclidean geometry, University of Toronto Press, Toronto

* Milnor, John W. (1982) Hyperbolic geometry: The first 150 years, Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. (N.S.) Volume 6, Number 1, pp. 9-24.

* Reynolds, William F. (1993) Hyperbolic Geometry on a Hyperboloid, American Mathematical Monthly 100:442-455.

* Stillwell, John. (1996) Sources in Hyperbolic Geometry, volume 10 in AMS/LMS series History of Mathematics.

* Samuels, David. (March 2006) Knit Theory Discover Magazine, volume 27, Number 3.

* James W. Anderson, Hyperbolic Geometry, Springer 2005, ISBN 1852339349

Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/"

All text is available under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License