Mounted Ouranosaurus skeleton, Museo di Storia Naturale di Venezia (Information about this image)

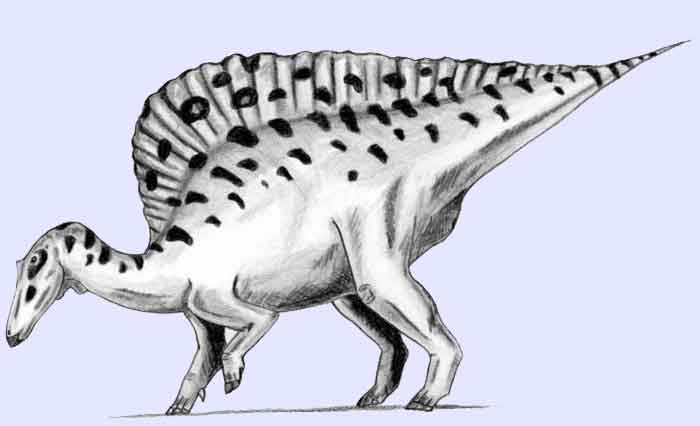

Ouranosaurus (meaning "brave (monitor) lizard") was an unusual iguanodont that lived during the early Cretaceous (late Aptian stage) about 110 million years ago in what is now Africa. Ouranosaurus measured about 7 meters long (24 ft) and weighed about 4 tons. Two complete fossils were found in the Echkar (or El Rhaz) Formation, Gadoufaouna deposits, Agadez, Niger, in 1966 and the animal was named in 1976 by French paleontologist Philippe Taquet.

Vertebrae

Ouranosaurus was once believed to have had a large sail on its back, supported by thick long spines, that spanned its entire back and tail, like Spinosaurus, a well-known meat-eating dinosaur that lived around the same time, and the older Dimetrodon of the Permian Period. The sail may have had blood vessels, and if so, the sail could have been held in the wind to heat or cool the dinosaur's circulating blood. In fact, the tall neural spines did not closely resemble those of sail-backs such as Dimetrodon. The supporting spines in a sailback become thinner distally, whereas in Ouranosaurus the spines actually become thicker distally. The spines were also bound together by tendons, which stiffened the back. Finally, the spine length peaks over the forelimbs. All of these features indicate that the dinosaur may have had a hump, resembling that of a bison or camel, rather than a sail. It could have been used as a source of nutrition when conditions were really harsh.

Body anatomy

On each hand it bore a thumb claw that was much smaller than the thumb claw of the earlier Iguanodon. The second third digits were broad and hoof-like, and anatomically were good for walking. To support the walking hypothesis, the wrist was large and the bones fused together to prevent its dislocation. The last digit (number 5) was long and presumably used for picking food like leaves and twigs or to help lower the food by lowering branch to a manageable height.

The hindlimbs were large and solid to accommodate the weight of the body. The femur was longer than the tibia, and the foot was small with only three toes. This leads to a conclussion of the legs being used as pillars and not for sprinting.

It had an unusual head with a much longer snout that its close relative Iguanodon; the snout was covered in a horny sheath when alive. The nasal passage was large and placed close to the beak. An anomaly with the skull were bumps found from the nasal opening to the top of the skull; their significance is unknown but they may have been used for socialisation or mating practices.

Ouranosaurus was an herbivore that had no teeth in the front portion of its jaws but a beak as in ducks and platypus. But the jaw teeth were large batteries of teeth on the sides of the jaws with Ouranosaurus used to chew up plant food with its sharp beak. The jaw also contained a predentary bone at the extreme front.

Temporal openings were found behind the eye and the larger Capiti-mandibularis muscle was attached to the coronid process on the jaw bone. The coronid process provided for a greater area of attachment for the jaw muscle allowing for more power and a stronger bite. A lesser muscle is located at the back of the skull and is named the Depressor mandibulae.

Life restoration of Ouranosaurus nigeriensis (Information about this image)

Classification

Although it shares some similarities with Iguanodon (such as a thumb spike), Ouranosaurus is no longer placed in Iguanodontidae, a grouping that is now considered paraphyletic. It is instead placed in the clade Hadrosauroidea, which contains the true hadrosaurs ("duck-billed dinosaurs") and their closest relatives. Ouranosaurus appears to have been an early specialised offshoot in this group. The type species is Ouranosaurus nigeriensis.

References

* Taquet, P. 1976. "Geologie et paleontologie du gisement de Gadoufaoua (Aptien du Niger)", Cahier Paleont., C.N.R.S. Paris, 1-191.

* Bailey, J.B. (1997). Neural spine elongation in dinosaurs: sailbacks or buffalo-backs? J. Paleontol. 71: 1124-1146.

* Dinosaurs and other Prehistoric Creatures, Edited by Ingrid Cranfield 2000 Salamander Books Ltd p 152-154

* Hazel Richardson. (2003): Dinosaurs and Other Prehistoric Animals (Smithsonian Handbooks). Pg.108, DK.

* Dixon, Dougal. "The Complete Book of Dinosaurs." Hermes House, 2006.

* Barry Cox, Colin Harrison, R.J.G. Savage, and Brian Gardiner. (1999): The Simon & Schuster Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Creatures: A Visual Who's Who of Prehistoric Life. Simon & Schuster.

External links

Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/"

All text is available under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License