Rhina ancylostoma (*) Cladus: Eukaryota Name Rhina ancylostoma (Bloch & Schneider, 1801) Synonyms * Squatina ancyclostoma Bloch & Schneider, 1801

* Bloch, M. E. and J. G. Schneider 1801: M. E. Blochii, Systema Ichthyologiae iconibus cx illustratum. Post obitum auctoris opus inchoatum absolvit, correxit, interpolavit Jo. Gottlob Schneider, Saxo. Berolini. Sumtibus Auctoris Impressum et Bibliopolio Sanderiano Commissum. M. E. Blochii, Systema Ichthyologiae: i-lx + 1-584, Pls. 1-110.

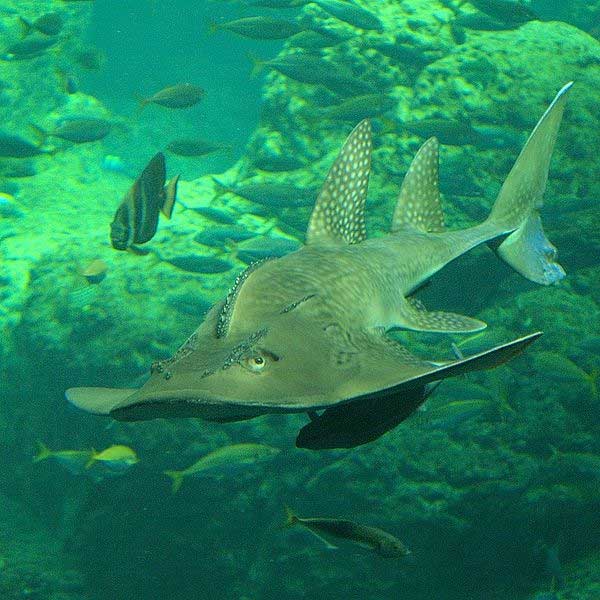

------- The bowmouth guitarfish, mud skate, or shark ray (Rhina ancylostoma, sometimes misgendered ancylostomus)[2] is a species of ray related to guitarfishes and skates, and the sole member of the family Rhinidae. It is found widely in the tropical coastal waters of the Indo-Pacific region, at depths of up to 90 m (300 ft). Highly distinctive in appearance, the bowmouth guitarfish has a wide, thick body with a blunt snout and large, shark-like dorsal and tail fins. The line of its mouth is strongly undulating, and there are multiple thorny ridges over its head and back. It has dorsal color pattern of many white spots over a bluish gray to brown background, with a pair of prominent markings over the pectoral fins. This large species can grow to 2.7 m (8.9 ft) long and 135 kg (300 lb). Strong-swimming and demersal in nature, the bowmouth guitarfish prefers sandy or muddy flats and areas adjacent to reefs, where it hunts for crustaceans, molluscs, and bony fishes. Reproduction is aplacental viviparous, with recorded litter sizes ranging from 4 to 9. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has assessed this species as Vulnerable; its sizable pectoral fins are greatly valued as food and it is widely caught by artisanal and commercial fisheries. Its thorns and propensity for damaging netted catches, however, cause it to be viewed as a nuisance by trawlers. Habitat destruction and degradation likely pose an additional, significant challenge to this species' survival. The bowmouth guitarfish adapts relatively well to captivity and is displayed in some public aquariums. Taxonomy and phylogeny German naturalists Marcus Elieser Bloch and Johann Gottlob Schneider originally described the bowmouth guitarfish in their 1801 Systema Ichthyologiae, based on a 51 cm (20 in) long specimen collected from off the Coromandel Coast of India, which has since been lost.[2][3] In his 1990 phylogenetic study, Kiyonori Nishida concluded that Rhina and Rhynchobatus are the sister clade to all other batoids except for the sawfishes.[4] John McEachran and Neil Aschliman (2004) found that, based on morphological characters, Rhina is the most basal member of the Rajiformes.[5] Systematists have variously classified the bowmouth guitarfish with the family Rhinobatidae (which was polyphyletic prior to recent revisions), Rhynchobatidae, or in its own family; the last was the arrangement recognized by Joseph Nelson in Fishes of the World (4th edition, 2006), as it has phylogenetic support.[5][6] Distribution and habitat Widely distributed in the tropical Indian and Pacific Oceans, the bowmouth guitarfish is found from KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa northward to the Red Sea, including the Seychelles. From there, its range extends eastward through the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia, including the Maldives, to as far north as southern Japan and Korea, and as far east as Papua New Guinea and northern Australia, where it occurs from Shark Bay in Western Australia to Sydney in New South Wales.[1][7] The bowmouth guitarfish inhabits coastal waters over a depth range of 3–90 m (10–300 ft). It is typically encountered on or near the bottom, though on occasion it may be seen swimming well above it. This species favors sandy or muddy habitats, and can also be found in the vicinity of rocky and coral reefs and shipwrecks.[8][9] Description The bowmouth guitarfish is large and heavily built, measuring up to 2.7 m (8.9 ft) in length and weighing 135 kg (300 lb).[10] The head is short, wide, and depressed, with a broadly rounded snout; the anterior portion of the head, including the eyes and large spiracles, is clearly distinct from the body. The nostrils are elongated and oriented nearly crosswise, with well-developed flaps of skin that separate each opening into inflow and outflow apertures. The lower jaw has three protruding lobes that fit into three depressions in the upper jaw.[7][8] There are around 47 upper tooth rows and 50 lower tooth rows; the teeth are ridged and arranged in winding bands.[10][11] The five pairs of gill slits are positioned underneath, close to the lateral margins of the head.[8] The body is deepest in front of the two dorsal fins, which are tall and falcate (sickle-shaped). The first dorsal fin is about a third larger than the second and originates over the pelvic fin origins, whereas the second dorsal is located midway between the first dorsal and the caudal fin. The pectoral fins are broad and triangular, with a deep indentation between their origins and the sides of the head. The pelvic fins are much smaller than the pectoral fins, and the anal fin is absent. The tail is much longer than the body, with a large, crescent-shaped caudal fin; the lower caudal fin lobe is more than half the length of the upper.[7][8][12] There is a thick ridge running along the midline of the back, bearing a band of massive, sharp thorns. More thorn-bearing ridges are found in front of the eyes, from over the eyes to behind the spiracles, and on the "shoulders". The entire dorsal surface has a granular texture from a dense covering of dermal denticles. The coloration is bluish gray above, lightening towards the margins of the head and pectoral fins, and light gray to white below. There are prominent white spots scattered over the body and fins, a white-edged black marking above each pectoral fin, and two dark transverse bands atop the head between the eyes. Younger individuals are more vividly colored than adults, which tend to be more brownish with a fainter pattern and proportionately smaller spots.[8] Biology and ecology The bowmouth guitarfish is an active species with a shark-like swimming style. It is most active at night, and is not known to be territorial.[13] This species has crushing dentition and feeds mainly on bottom-dwelling crustaceans, such as crabs and shrimp, though molluscs and bony fishes are also consumed.[1][10][9] The bowmouth guitarfish is known to fall prey to the tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier).[14] The thorns on its head and back are employed in defense (including butting).[10] Parasites that have been documented from this species include the tapeworm Tylocephalum carnpanulatum,[15] the trematode Melogonimus rhodanometra,[16] the monogeneans Branchotenthes robinoverstreeti and Monocotyle ancylostomae,[17][18] and the copepod Nesippus vespa.[19] There is a record of an individual being serviced by bluestreak cleaner wrasses (Labroides dimidiatus). This species is aplacental viviparous, with the developing embryos being sustained by yolk. Michael (1993) reported the litter size as 4 and the birth size as 45 cm (18 in), while Last and Stevens (2009) noted a female specimen pregnant with 9 mid-term embryos, measuring 27–31 cm (11–12 in) long. Males attain sexual maturity at 1.5–1.8 m (4.9–5.9 ft) long.[9][8] Human interactions Throughout its range, the bowmouth guitarfish is captured intentionally and incidentally by artisanal and commercial fisheries, using trawls, gillnets, and line gear. The pectoral fins are exceedingly valuable and usually the only part brought to market, though the meat is sometimes also sold fresh or dried and salted in Asia for human consumption.[1][10][12] Larger bowmouth guitarfish are considered a nuisance by trawl fishers, as their rough skin and thorns make them difficult to handle and may damage the rest of the catch.[8] In Thailand, the enlarged thorns of this species are used to make bracelets.[20] The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has assessed the bowmouth guitarfish as Vulnerable; it is threatened by fishing and habitat destruction and degradation, particularly from blast fishing, coral bleaching, and siltation. Its numbers are known to have declined in Indonesian waters, where it is targeted by guitarfish gillnet fisheries. The bowmouth guitarfish has been assessed as Near Threatened off Australia, where it is not a targeted species but is taken as bycatch. The installation of turtle excluder devices (TEDs) on some Australian trawlers has benefited this species.[1] The bowmouth guitarfish is a popular subject of public aquariums and fares relatively well, with one individual having lived for 7 years in captivity.[8][9] Rare and facing many conservation threats, it has been called "the panda of the aquatic world".[21] In 2007, the Newport Aquarium initiated the world's first captive breeding program for this species.[21] References 1. ^ a b c d e McAuley, R. and L.J.V. Compagno (2003). Rhina ancylostoma. In: IUCN 2003. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on January 21, 2010.

Source: Wikispecies, Wikipedia: All text is available under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License |

|